Image

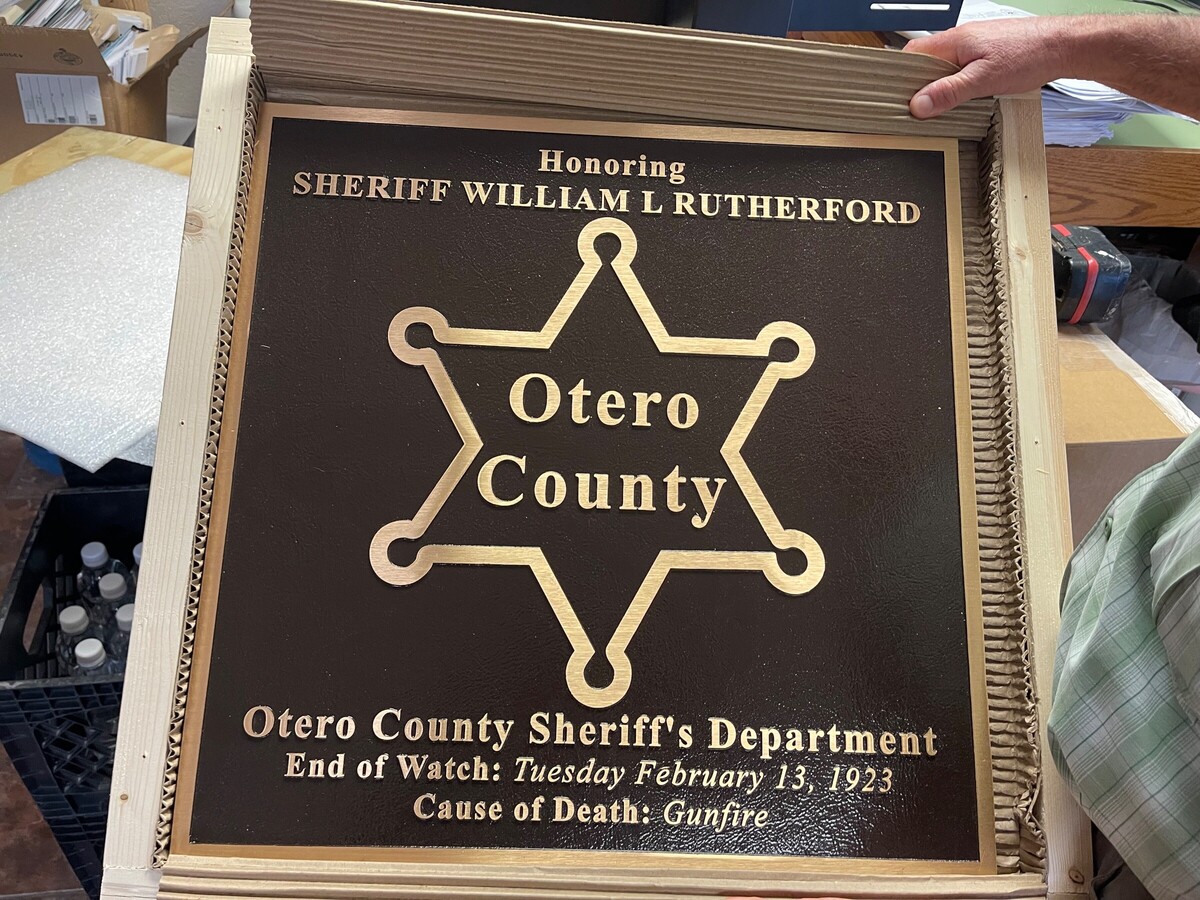

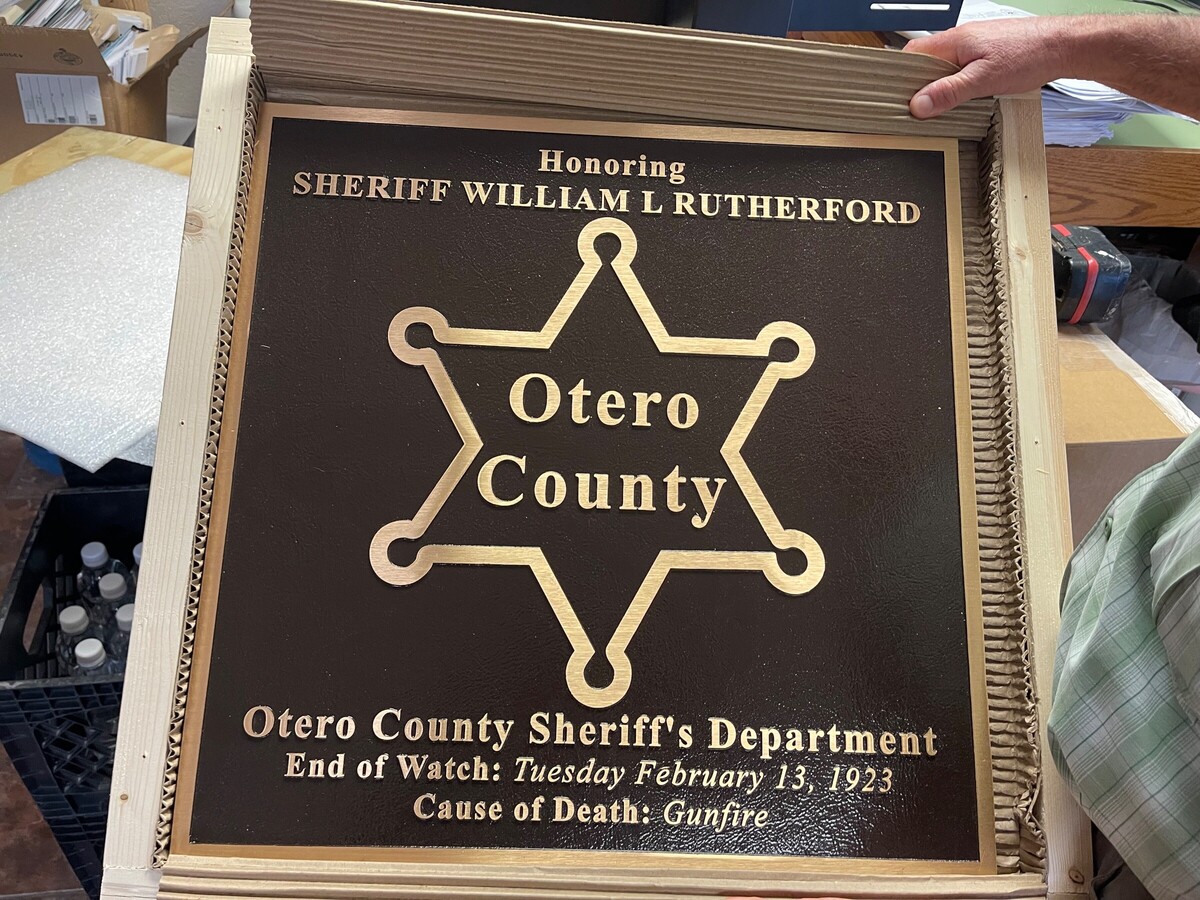

More than a century since the death of Otero County Sheriff Bill Sheriff Rutherford, he is going to be honored as part of the Alamogordo MainStreet Makeover corridor revitalization. A bronze plaque will soon be embedded in the median near the site of the shooting in front of the Avis building near 10th Street on New York Avenue marking the exact location where Rutherford fell in the line of duty so many years ago.

The memorial was inspired by a conversation between 2nd Life Media AlamogordoTownNews.org journalist, Chris Edwards and local history enthusiast, Michael Shyne. Shyne’s deep passion for history and this story moved Edwards to action. Inspired by the story, he was motivated to partner and preserve the story for the next generation of visitors on New York Avenue itself. In partnership with Alamogordo MainStreet and the owners of General Hydronics Utilities—Ed Boles and Charlie Martin—who made a generous contribution to fund the plaque and its installation, the memorialization is becoming a reality.

A simple converation, between Mr. Shyne and Mr. Edwards and their care for preservation of history, stories and legends sparked an idea that is becoming a reality.

The tribute is part of a broader effort to preserve Alamogordo’s civic memory and honor those who shaped its history by Alamogordo MainStreet, the Tularosa Basin Historic Society and 2nd Life Media. As New York Avenue undergoes rehabilitation, the story of Sheriff Rutherford will be etched into the streetscape—reminding future generations of the cost of public service and the resilience of a community that came together in the face of tragedy.

First Officer Down In Alamogordo Founded in 1912

In the chill of early February 13th, 1923, two young thieves—William G. LaFavers (also recorded as LaFaver, LaFavors, or LaFores), age 19, and Charles Hollis Smelcer (alias Buck Smitzer), age 21—stole a saddle and other tack from a rancher in northern Lincoln County. Arrested and sentenced in Corona they were bound for jail in Carrizozo under the custody of Deputies A.S. McCamant and Graciano Yrait.

The journey turned violent. Somewhere along the rough road, LaFavers lunged for McCamant’s pistol. The two men tumbled from the Ford touring car, and LaFavers seized the weapon. Smelcer attacked Yrait, but was losing until LaFavers intervened at gunpoint. The fugitives debated killing the deputies, then forced them to walk away under threat of a rifle. The officers trekked 12 miles to the nearest telephone.

The escapees headed south, stopping in Carrizozo to buy .30-30 caliber ammunition, then continued to Tularosa for car repairs before pressing on toward Alamogordo.

On the evening of February 13, Otero County Sheriff Bill Rutherford returned from Santa Fe. Around 8:30 p.m., he received a call from Lincoln County Deputy Harry Straley warning that LaFavers and Smelcer were armed and dangerous and could be headed to Alamogordo. Moments later, Rutherford stepped out of the Warren Drug Store at 10th Street and New York Avenue and spotted an open air Ford matching the description. Two men sat inside.

“If you have no objection, I would like to search this car,” a witness recalled Rutherford saying.

The car lurched backward, then surged forward. Rutherford stepped onto the running board and reached inside. A loud bang rang out. Witnesses on New York Avenue and from within the drug store, thought a tire had burst, but Rutherford collapsed in the street, shot in the neck. The Ford jumped the curb and sped away. Local resident O.M. Smith rushed to the sheriff’s side in the hopes of saving him, but Sheriff Rutherford was already dead. Strangely, his hat had vanished.

News of the murder spread rapidly. Former Sheriff Howard Beacham and car dealer Shorty Miller sped south on the Orogrande Road. Deputy H.M. Denny and citizen Louis Wolfinger headed southwest. District Attorney J. Benson Newell coordinated the search, alerting authorities across the region. A tourist arriving from the south reported passing a Ford touring car traveling at high speed.

Miller’s Buick ran out of gas north of Orogrande, forcing him and Beacham to walk into town. By midnight, officers located the Lincoln County Ford. A posse with tracking dogs was assembled, but the trail ended at the railroad tracks. Troops from Fort Bliss arrived at dawn, and joined the search. A special train from Alamogordo delivered horse-mounted posse members, while another train brought Lincoln County deputies.

Later that day, searchers found a sheep-lined coat taken from one of the deputies. The manhunt intensified. In the early afternoon, posse member M.L. Bradford, on horseback, spotted the fugitives. They opened fire, hitting Bradford in the leg. He returned fire but missed. Surrounded by more posse members, the fugitives raised a white cloth in surrender and laid down their weapons.

They had traveled roughly 15 miles from where they abandoned the car, circling back toward the El Paso Road in hopes of stealing another vehicle. By 6:45 p.m. on February 14, LaFavers and Smelcer were locked in the Otero County jail.

Smelcer was wearing Sheriff Rutherford’s hat, the very one missing from the scene of the muder on New York Avenue.

On February 26, a grand jury indicted both men for first-degree murder. Their trial began in Alamogordo on March 1—just 23 days after the killing. The jury deliberated for only 35 minutes before returning a guilty verdict. On March 3, they were sentenced to hang on April 6 in the jail yard located at the 1100 block of New York Avenue behind the present day court house.

Defense attorneys appealed, but before the case reached a higher court, Governor James Hinkle commuted Smelcer’s sentence to 40–50 years and LaFavers’ to life.

To the dismay of locals in Alamogordo and in disbelief both were evenutally parolled and pardoned.

Both William G. LaFavers and Charles Hollis Smelcer were convicted of first-degree murder for the 1923 killing of Otero County Sheriff Bill Rutherford. They were sentenced to hang, but their sentences were commuted and later pardoned by two different governors:

Charles Smelcer: Sentence commuted to 40–50 years by Governor Arthur Seligman in 1932; pardoned in 1932.

William LaFavers: Paroled to Amarillo in 1936; pardoned by Governor John E. Miles in 1939.

While no direct public statements from either governor explicitly justify the pardons, several contextual factors help explain the decisions:

Governor Arthur Seligman (1931–1933) was soft on crime who emphasized rehabilitation over retribution. His administration supported veterans, education, and economic recovery during the Great Depression. His scrapbooks and papers include references to pardons and clemency as part of broader criminal justice reform that he championed during his tenure to end the perceptions of New Mexico as the wild west.

Governor John E. Miles (1939–1943), was also known for his populist leanings and support for leniency in cases where rehabilitation was evident. LaFavers had served over a decade and was reportedly a model prisoner thus Miles leaned into the idea of reform over retibution.

By the time of their pardons there were expected to just live another few years as the life expentancy of men their age was just 48.1 years in New Mexico at the time. Smelcer had served nearly a decade and was paroled to California before receiving a full pardon. LaFavers had served over 13 years and was paroled to Texas before his pardon. Governors often considered time served, age, live expentency, and conduct in prison when granting clemency.

Defense attorneys had appealed the convictions early on, and while the appeals were never fully adjudicated, the legal pressure may have influenced executive decisions. Additionally, public attention to the case had waned by the 1930s, and the political cost of clemency was likely lower.

At the time, New Mexico did not have a formal “life without parole” sentence. Clemency was often the only mechanism for adjusting harsh sentences over time.

Remembering History in the 21st Century

The pardons remain controversial, especially given the gravity of the crime. Yet they reflect a broader trend in early 20th-century governance—one that sought to balance justice with mercy and grappled with evolving standards of punishment and rehabilitation. But beyond the legal complexities lies a deeper truth: a well-respected Sheriff of Otero County was murdered in cold blood, becoming the first fallen officer in the young and growing city of Alamogordo. His sacrifice marked a turning point in local history, and now, more than a century later, Sheriff Bill Rutherford will be permanently honored as part of the New York Avenue revitalization.

Thanks to the passion of local historian Michael Shyne, the advocacy of journalist Chris Edwards, the commitment of Alamogordo MainStreet and the City of Alamogordo’s Dr. Stephanie Hernandez, Justen Boyle and Mayor Pro Tem Sharon McDonald, and the generosity of General Hydronics Utilities - Ed Boles and Charlie Martin, a bronze plaque will soon be embedded near the very spot where Rutherford fell—etched into the heart of Alamogordo’s civic memory.

Note: To learn more about other fallen officers from Alamogordo, visit the Alamogordo Fallen Officer Memorial, located on 10th Street at the eastern edge of the MainStreet District, adjacent to the New Mexico State Police Headquarters. This solemn tribute honors the lives and service of local law enforcement officers who made the ultimate sacrifice in the line of duty. The memorial stands as a reminder of Alamogordo’s enduring respect for public service and community protection. It complements the soon to be commissioned plaque for Sheriff Bill Rutherford, embedding his legacy into the very streets where history unfolded.

For additional stories and historical context, visit AlamogordoTownNews.org or explore the archives at the Alamogordo Public Library or the Tularosa Basin Museum of History located at 10th and White Sands Blvd.