Image

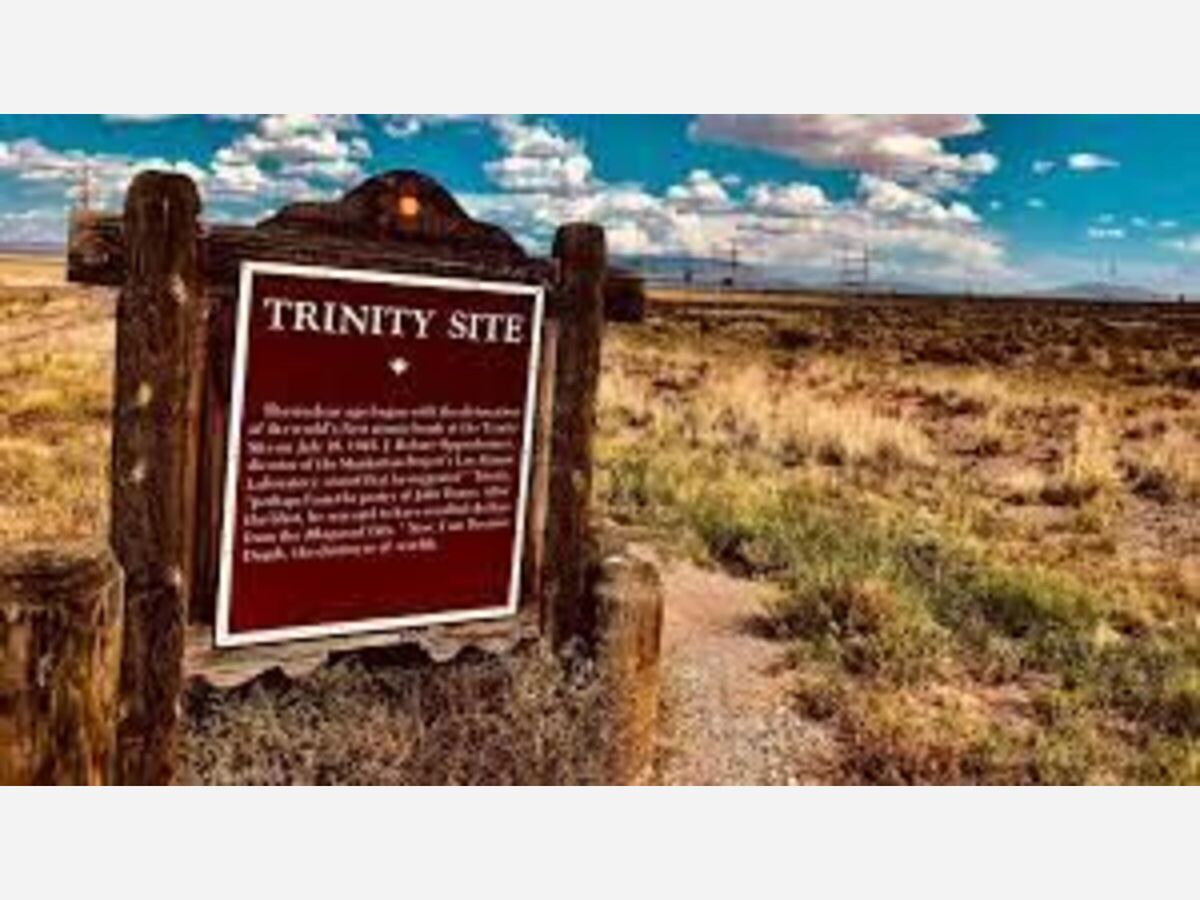

The Trinity Site near Alamogordo, New Mexico at White Sands Missile Proving Ground New White Sands Missile Range is a spot of historical significance that changed the world, the outcome of World War 2 and impacts sociopolitical dialog around the globe to this day. Tours are limited to 1 day a year. This year October 2nd, 2021 from 8 am to 3:30 pm.

What is the history of the Trinity Site?

On August 6, 1945, the United States dropped a nuclear weapon on Hiroshima, Japan – the first time such weapon of mass destruction that was ever used in conflict. Three days later the U.S. released another on Nagasaki, devastating the city and ushering in the nuclear age.

By 1945, the scientists of the Manhattan Project centered in Los Alamos, New Mexico with Oak Ridge Laboratories in Tennessee and the University of Chicago labs working to develop and build a nuclear weapon had made significant progress.

Employees of the top-secret project via it's 3 locations developed two types of atom bombs. One used uranium and a fairly simple design, leaving scientists confident it did not need testing. The other was a more complex implosion design using plutonium. Project leaders decided this second bomb needed to be tested before it was deemed ready for use.

On July 16, 1945, the first atomic bomb successfully detonated at the Trinity test site.

Seeking an isolated test site for both safety and secrecy, planners chose a flat desert region at a U.S. Air Force base near Alamogordo, New Mexico called White Sands Proving Ground. This was a top secret military base where missile, aircraft and bomb testing took place and still does to this very day.

While the test site was relatively barren, the nearest town of Carrizozo was just over twenty miles away.

As the test date approached, concerns grew over the possible effects of radioactive fallout on nearby towns.

After receiving warnings over potential legal liabilities, Manhattan Project Director General Leslie Groves tasked the Army with setting up an offsite monitoring system and preparing evacuation plans for those in a forty-mile radius.

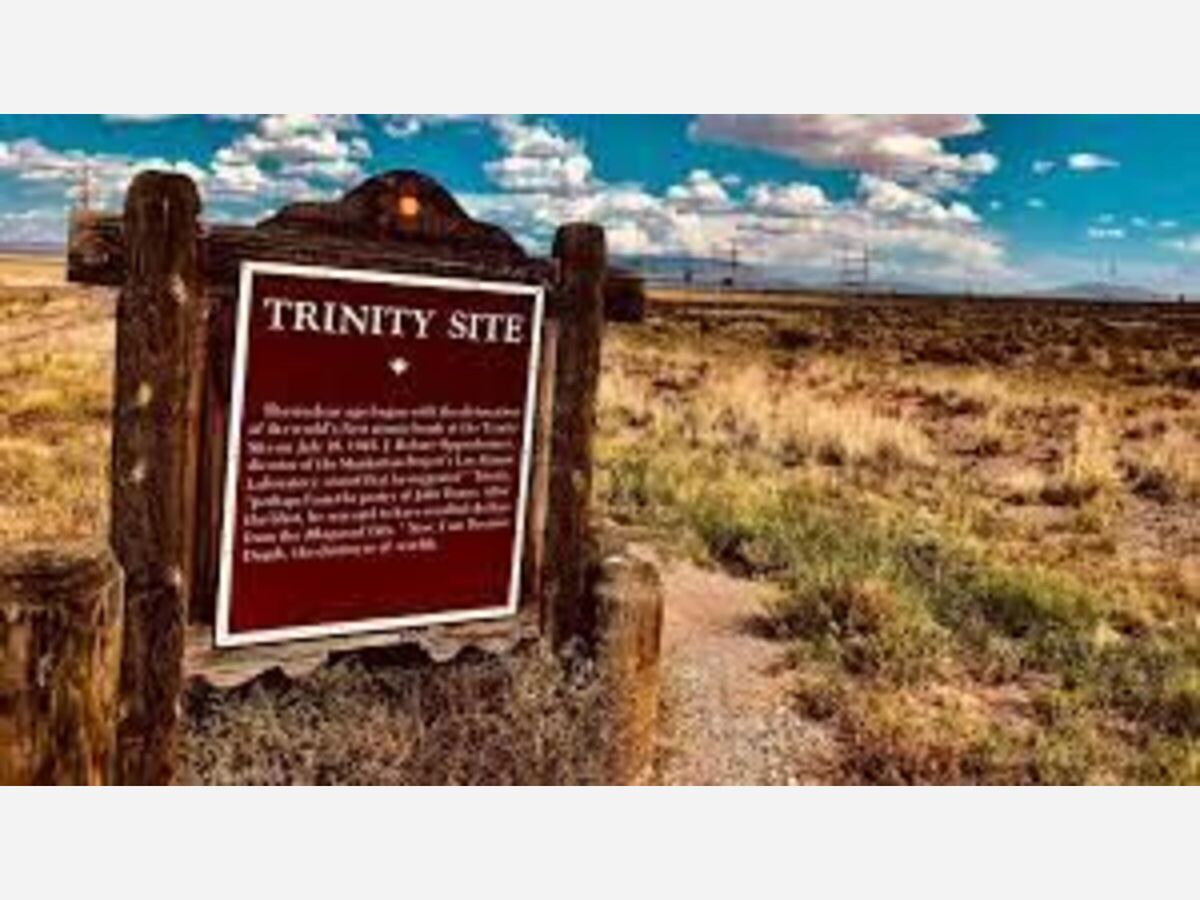

The morning of July 16, the test weapon – referred to as “the gadget” – sat atop a 100-foot tower. Key observers were stationed in the control shelter constructed about 6 miles from the point of explosion. Others observed from shelters similarly situated around the test site, from base camp ten miles away, from “Hill Station” twenty miles away or from the air in B-29 bombers. Thunderstorms in the area delayed the test until early morning. At 5:30 am, the plutonium bomb detonated.

Video of Explosion and First Atomic Bomb Test in History

The term "Gadget" was a laboratory euphemism for a bomb, from which the laboratory's weapon physics division, "G Division", took its name in August 1944. At that time it did not refer specifically to the Trinity Test device as it had yet to be developed, but once it was, it became the laboratory code name. The Trinity Gadget was officially a Y-1561 device, as was the Fat Man used a few weeks later in the bombing of Nagasaki. The two were very similar, with only minor differences, the most obvious being the absence of fuzing and the external ballistic casing. The bombs were still under development, and small changes continued to be made to the Fat Man design.

To keep the design as simple as possible, a near solid spherical core was chosen rather than a hollow one, although calculations showed that a hollow core would be more efficient in its use of plutonium. The core was compressed to prompt super-criticality by the implosion generated by the high explosive lens. This design became known as a "Christy Core" or "Christy pit" after physicist Robert F. Christy, who made the solid pit design a reality after it was initially proposed by Edward Teller. Along with the pit, the whole physics package was also informally nicknamed "Christy['s] Gadget".

Of the several allotropes of plutonium, the metallurgists preferred the malleable δ (delta) phase. This was stabilized at room temperature by alloying it with gallium. Two equal hemispheres of plutonium-gallium alloy were plated with silver, and designated by serial numbers HS-1 and HS-2. The 6.19-kilogram (13.6 lb) radioactive core generated 15 W of heat, which warmed it up to about 100 to 110 °F (38 to 43 °C), and the silver plating developed blisters that had to be filed down and covered with gold foil; later cores were plated with nickel instead. The Trinity core consisted of just these two hemispheres. Later cores also included a ring with a triangular cross-section to prevent jets forming in the gap between them.

Basic nuclear components of the Gadget. The uranium slug containing the plutonium sphere was inserted late in the assembly process.

A trial assembly of the Gadget without the active components or explosive lenses was carried out by the bomb assembly team headed by Norris Bradbury at Los Alamos on July 3. It was driven to Trinity and back. A set of explosive lenses arrived on July 7, followed by a second set on July 10. Each was examined by Bradbury and Kistiakowsky, and the best ones were selected for use. The remainder were handed over to Edward Creutz, who conducted a test detonation at Pajarito Canyon near Los Alamos without nuclear material. This test brought bad news: magnetic measurements of the simultaneity of the implosion seemed to indicate that the Trinity test would fail. Bethe worked through the night to assess the results and reported that they were consistent with a perfect explosion.

Assembly of the nuclear capsule began on July 13 at the McDonald Ranch House, where the master bedroom had been turned into a clean room. The polonium-beryllium "Urchin" initiator was assembled, and Louis Slotin placed it inside the two hemispheres of the plutonium core. Cyril Smith then placed the core in the uranium tamper plug, or "slug". Air gaps were filled with 0.5-mil (0.013 mm) gold foil, and the two halves of the plug were held together with uranium washers and screws which fit smoothly into the domed ends of the plug. The completed capsule was then driven to the base of the tower.

Louis Slotin and Herbert Lehr with the Gadget prior to insertion of the tamper plug (visible in front of Lehr's left knee)

At the tower, a temporary eyebolt was screwed into the 105-pound (48 kg) capsule and a chain hoist was used to lower the capsule into the gadget. As the capsule entered the hole in the uranium tamper, it stuck. Robert Bacher realized that the heat from the plutonium core had caused the capsule to expand, while the explosives assembly with the tamper had cooled during the night in the desert. By leaving the capsule in contact with the tamper, the temperatures equalized and, in a few minutes, the capsule had slipped completely into the tamper. The eyebolt was then removed from the capsule and replaced with a threaded uranium plug, a boron disk was placed on top of the capsule, an aluminum plug was screwed into the hole in the pusher, and the two remaining high explosive lenses were installed. Finally, the upper Dural polar cap was bolted into place. Assembly was completed at about 16:45 on July 13.

The Gadget was hoisted to the top of a 100-foot (30 m) steel tower. The height would give a better indication of how the weapon would behave when dropped from a bomber, as detonation in the air would maximize the amount of energy applied directly to the target (as the explosion expanded in a spherical shape) and would generate less nuclear fallout. The tower stood on four legs that went 20 feet (6.1 m) into the ground, with concrete footings. Atop it was an oak platform, and a shack made of corrugated iron that was open on the western side. The Gadget was hauled up with an electric winch. A truckload of mattresses was placed underneath in case the cable broke and the Gadget fell. The seven-man arming party, consisting of Bainbridge, Kistiakowsky, Joseph McKibben and four soldiers including Lieutenant Bush, drove out to the tower to perform the final arming shortly after 22:00 on July 15.

The scientists wanted good visibility, low humidity, light winds at low altitude, and westerly winds at high altitude for the test. The best weather was predicted between July 18 and 21, but the Potsdam Conference was due to start on July 16 and President Harry S. Truman wanted the test to be conducted before the conference began. It was therefore scheduled for July 16, the earliest date at which the bomb components would be available.

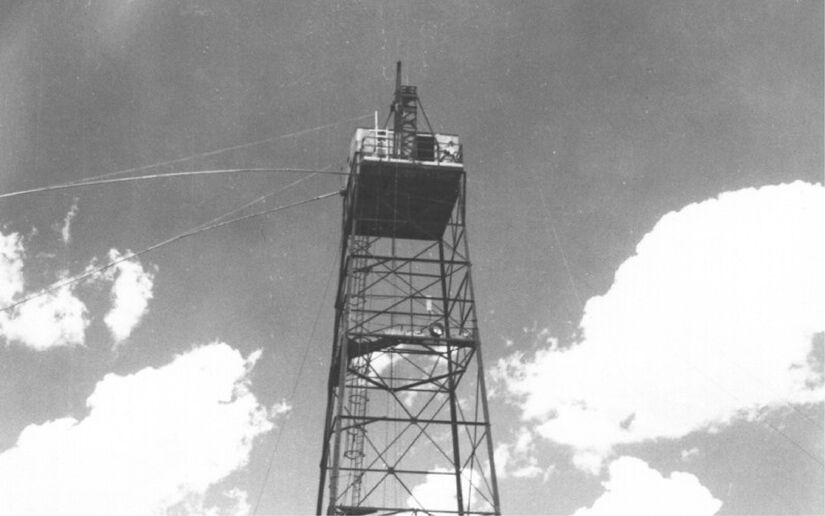

The Trinity explosion, 16 ms after detonation. The viewed hemisphere's highest point in this image is about 200 metres (660 ft) high.

The detonation was initially planned for 04:00 MWT but was postponed because of rain and lightning from early that morning. It was feared that the danger from radiation and fallout would be increased by rain, and lightning had the scientists concerned about a premature detonation.[89] A crucial favorable weather report came in at 04:45,and the final twenty-minute countdown began at 05:10, read by Samuel Allison.By 05:30 the rain had gone.There were some communication problems. The shortwave radio frequency for communicating with the B-29s was shared with the Voice of America, and the FM radios shared a frequency with a railroad freight yard in San Antonio, Texas

Two circling B-29s observed the test, with Shields again flying the lead plane. They carried members of Project Alberta, who would carry out airborne measurements during the atomic missions. These included Captain Deak Parsons, the Associate Director of the Los Alamos Laboratory and the head of Project Alberta; Luis Alvarez, Harold Agnew, Bernard Waldman, Wolfgang Panofsky, and William Penney. The overcast sky obscured their view of the test site.

At 05:29:21 MWT (± 15 seconds), the device exploded with an energy equivalent to around 22 kilotons of TNT (92 TJ). The desert sand, largely made of silica, melted and became a mildly radioactive light green glass, which was named trinitite. The explosion created a crater approximately 4.7 feet (1.4 m) deep and 88 yards (80 m) wide. The radius of the trinitite layer was approximately 330 yards (300 m). At the time of detonation, the surrounding mountains were illuminated "brighter than daytime" for one to two seconds, and the heat was reported as "being as hot as an oven" at the base camp. The observed colors of the illumination changed from purple to green and eventually to white. The roar of the shock wave took 40 seconds to reach the observers. It was felt over 100 miles (160 km) away, and the mushroom cloud reached 7.5 miles (12.1 km) in height.

Ralph Carlisle Smith, watching from Compania Hill, wrote:

I was staring straight ahead with my open left eye covered by a welder's glass and my right eye remaining open and uncovered. Suddenly, my right eye was blinded by a light which appeared instantaneously all about without any build up of intensity. My left eye could see the ball of fire start up like a tremendous bubble or nob-like mushroom. I dropped the glass from my left eye almost immediately and watched the light climb upward. The light intensity fell rapidly, hence did not blind my left eye but it was still amazingly bright. It turned yellow, then red, and then beautiful purple. At first it had a translucent character, but shortly turned to a tinted or colored white smoke appearance. The ball of fire seemed to rise in something of toadstool effect. Later the column proceeded as a cylinder of white smoke; it seemed to move ponderously. A hole was punched through the clouds, but two fog rings appeared well above the white smoke column. There was a spontaneous cheer from the observers. Dr. von Neumann said, "that was at least 5,000 tons and probably a lot more."

In his official report on the test, Farrell (who initially exclaimed, "The long-hairs have let it get away from them!") wrote:

"The lighting effects beggared description. The whole country was lighted by a searing light with the intensity many times that of the midday sun. It was golden, purple, violet, gray, and blue. It lighted every peak, crevasse and ridge of the nearby mountain range with a clarity and beauty that cannot be described but must be seen to be imagined ..."

William L. Laurence of The New York Times had been transferred temporarily to the Manhattan Project at Groves's request in early 1945. Groves had arranged for Laurence to view significant events, including Trinity and the atomic bombing of Japan. Laurence wrote press releases with the help of the Manhattan Project's public relations staff. He later recalled that

"A loud cry filled the air. The little groups that hitherto had stood rooted to the earth like desert plants broke into dance, the rhythm of primitive man dancing at one of his fire festivals at the coming of Spring."

Original color-exposed photograph by Jack Aeby, July 16, 1945.

After the initial euphoria of witnessing the explosion had passed, Bainbridge told Oppenheimer, "Now we are all sons of bitches."

Rabi noticed Oppenheimer's reaction: "I'll never forget his walk"; Rabi recalled, "I'll never forget the way he stepped out of the car ... his walk was like High Noon ... this kind of strut. He had done it."

Joan Hinton, a graduate student working on the Manhattan Project, described the explosion:

“It was like being at the bottom of an ocean of light. We were bathed in it from all directions. The light withdrew into the bomb as if the bomb sucked it up. Then it turned purple and blue and went up and up and up. We were still talking in whispers when the cloud reached the level where it was struck by the rising sunlight so it cleared out the natural clouds. We saw a cloud that was dark and red at the bottom and daylight at the top. Then suddenly the sound reached us. It was very sharp and rumbled and all the mountains were rumbling with it.”

The explosive force was equal to roughly 20,000 tons of TNT, far larger than the expected 7,500 tons. The flash of light was visible over 280 miles from the test site; the blast broke windows 120 miles away. Military police in nearby towns told those who saw the flash that an ammunition dump had exploded.

Radioactive green glass created from some of the dirt and debris caught in the fireball littered the test ground. Reports of public radiation exposure in the days following the test and evidence indicating high rates of infant mortality in counties downwind from the test site were largely ignored though officials did decide to forego further testing at the site in favor of a larger, more barren space. Residents of southern New Mexico are still pushing for the government to acknowledge and take responsibility for the lasting effects of the Trinity test, as detailed in a new report on the decades of health issues and deaths in the region.

Following the successful test, word was sent to U.S. Secretary of War Henry Stimson who relayed the news to President Truman. It was clear to everyone the most destructive weapon ever built by humankind was ready for war.

The exact origin of the code name "Trinity" for the test is unknown, but it is often attributed to Oppenheimer as a reference to the poetry of John Donne, which in turn references the Christian notion of the Trinity (i.e., the three persons constituting the nature of God). In 1962, Groves wrote to Oppenheimer about the origin of the name, asking if he had chosen it because it was a name common to rivers and peaks in the West and would not attract attention, and elicited this reply:

I did suggest it, but not on that ground ... Why I chose the name is not clear, but I know what thoughts were in my mind. There is a poem of John Donne, written just before his death, which I know and love. From it a quotation:

As West and East

In all flatt Maps—and I am one—are one,

So death doth touch the Resurrection.That still does not make a Trinity, but in another, better known devotional poem Donne opens,

Batter my heart, three person'd God.

Visits to the Trinity Site:

In September 1953, about 650 people attended the first Trinity Site open house. Visitors to a Trinity Site open house are allowed to see the ground zero and McDonald Ranch House areas.

More than seventy years after the test, residual radiation at the site was about ten times higher than normal background radiation in the area. The amount of radioactive exposure received during a one-hour visit to the site is about half of the total radiation exposure which a U.S. adult receives on an average day from natural and medical sources.

On December 21, 1965, the 51,500-acre (20,800 ha) Trinity Site was declared a National Historic Landmark district, and on October 15, 1966, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The landmark includes the base camp, where the scientists and support group lived; ground zero, where the bomb was placed for the explosion; and the McDonald ranch house, where the plutonium core to the bomb was assembled. One of the old instrumentation bunkers is visible beside the road just west of ground zero. An inner oblong fence was added in 1967, and the corridor barbed wire fence that connects the outer fence to the inner one was completed in 1972. Jumbo was moved to the parking lot in 1979; it is missing its ends from an attempt to destroy it in 1946 using eight 500-pound (230 kg) bombs. The Trinity monument, a rough-sided, lava-rock obelisk about 12 feet (3.7 m) high, marks the explosion's hypocenter. It was erected in 1965 by Army personnel from the White Sands Missile Range using local rocks taken from the western boundary of the range.

A simple metal plaque reads:

Trinity Site

Where

the World's First

Nuclear Device

Was Exploded on

July 16, 1945

Erected 1965

White Sands Missile Range

J. Frederick Thorlin

Major General U.S. Army

Commanding

A second memorial plaque on the obelisk was prepared by the Army and the National Park Service, and was unveiled on the 30th anniversary of the test in 1975. It reads:

Trinity Site

Has Been Designated a

National

Historic Landmark

This Site possesses National Significance

in Commemorating the History of the

United States of America

1975

National Park Service

United States Department of the Interior

Visitors to the Trinity site in 1995 for 50th anniversary

A special tour of the site was conducted on July 16, 1995, to mark the 50th anniversary of the Trinity test. About 5,000 visitors arrived to commemorate the occasion, the largest crowd for any open house.

Since then, the open houses have usually averaged two to three thousand visitors. The site is still a popular destination for those interested in atomic tourism, though it is only open to the public twice a year during the Trinity Site Open House on the first Saturdays of April and October. Due to Covid-19 restriction the site has been closed the last year to visits.

In 2014, the White Sands Missile Range announced that due to budgetary constraints, the site would only be open once a year, on the first Saturday in April. In 2015, this decision was reversed, and two events were scheduled, in April and October. The base commander, Brigadier General Timothy R. Coffin, explained that:

Trinity Site is a national historic testing landmark where the theories and engineering of some of the nation's brightest minds were tested with the detonation of the first nuclear bomb, technologies which then helped end World War II. It is important for us to share Trinity with the public even though the site is located inside a very active military test range. We have travelers from as far away as Australia who travel to visit this historic landmark. Facilitating access twice per year allows more people the chance to visit this historic site

To visit the Trinity Location Opened October 2nd, 2021 from 8 am to 3:30 pm

Stallion Gate Entrance

Exit I-25 on mile marker 139 (San Antonio, N.M.) and head 12 miles east or exit U.S. Highway 54 onto U.S. Highway 380 and head west 53 miles of Carrizozo, N.M. Turn south on New Mexico State Highway 525 and head south five miles to the Stallion gate.

Alamogordo Caravan

Alamogordo Alternative - The Alamogordo Chamber of Commerce sponsors a caravan for visitors to Trinity Site. The Alamogordo caravan meeting site is at the Tularosa High School Athletic Field Parking lot. Turn west off Hwy. 54/70 in Tularosa at Higuero St. Proceed west to La Luz Ave. Turn right on La Luz Ave. (north) to athletic field.

Vehicle line up will begin at 7 a.m. Caravan departs at 8 a.m. NO STRAGGLERS WILL BE ALLOWED INTO THE CARAVAN ONCE THE LAST PERSON IN THE CARAVAN HAS BEEN IDENTIFIED.

Visitors entering this way will travel as an escorted group to and from Trinity Site. The drive is 145 miles roundtrip and there are no service station facilities on the missile range. Please make sure you have a full tank of gas.

The caravan is scheduled to leave Trinity Site at 12:30 for the return to Tularosa.

Cameras are allowed at Trinity Site but their use is strictly prohibited anywhere else on White Sands Missile Range.

Official Press Release:

Trinity Site Open House is set for Oct. 2

WHITE SANDS MISSILE RANGE, N.M. (July 9, 2021) – White Sands Missile Range will open Trinity Site to the public after a brief pause in activities due to COVID-19 on Oct. 2. Trinity Site is where the world’s first atomic bomb was tested at 5:29:45 a.m. Mountain War Time July 16, 1945.

The open house is free and no reservations are required. At the site visitors can take a quarter-mile walk to ground zero where a small obelisk marks the exact spot where the bomb was detonated. Historical photos are mounted on the fence surrounding the area.

While at the site, visitors can also ride a missile range shuttle bus two miles from ground zero to the Schmidt/McDonald Ranch House. The ranch house is where the scientists assembled the plutonium core of the bomb. Visitors will also be able to experience what life was like for a ranch family in the early 1940s.

The simplest way to get to Trinity Site is to enter White Sands Missile Range through its Stallion Range Center gate. Stallion gate is five miles south of U.S. Highway 380. The turnoff is 12 miles east of San Antonio, New Mexico, and 53 miles west of Carrizozo, New Mexico. The nearest city to make hotel reservations is Socorro, New Mexico. The Stallion Gate is open from 8 a.m. to 2 p.m. Visitors arriving at the gate between those hours will be allowed to drive unescorted the 17 miles to Trinity Site. The road is paved and marked. The site closes promptly at 3:30 p.m.

Media who would like to visit the open house must register by calling the Public Affairs Office at 575-678-1134.

For more information on the open house please visit the Trinity Site website at: Trinity Site Information

White Sands Missile Range, DoD's largest, fully-instrumented, open air range, provides America's Armed Forces, allies, partners, and defense technology innovators with the world's premiere research, development, test, evaluation, experimentation, and training facilities to ensure our nation's defense readiness.

This article is available as a Podcast to listen click here

Author Chris Edwards

Sources: Earth Zero, US Army Press Release, US Air Force Press Releases, US Army Archives, Smithsonian Online Data Base, Wikipedia, "Trinity Site". White Sands Missile Range. Archived from the original on June 1, 2008. Retrieved July 16, 2007. GPS Coordinates for obelisk (exact GZ) = 33°40.636′N106°28.525′W, Jump up to:a b Hoddeson et al. 1993, p. 311., "Trinity Site History: A copy of the brochure given to site visitors". White Sands Missile Range, United States Army. Archived from the original on August 31, 2014., "Nuclear Events and Their Consequences". Borden Institute. "... approximately 82% of the fission energy is released as kinetic energy of the two large fission fragments. These fragments, being massive and highly charged particles, interact readily with matter. They transfer their energy quickly to the surrounding weapon materials, which rapidly become heated"^ "Nuclear Engineering Overview" (PDF). Technical University Vienna. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 15, 2018., "Fact Sheet – Operation Trinity" (PDF). Defense Threat Reduction Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 25, 2014. Retrieved November 15, 2014., Wellerstein, Alex (November 10, 2014). "The Fat Man's uranium". Restricted Data: The Nuclear Secrecy Blog. Retrieved November 15, 2014., Hanson, Susan K.; Pollington, Anthony D.; Waidmann, Christopher R.; Kinman, William S.; Wende, Allison M.; Miller, Jeffrey L.; Berger, Jennifer A.; Oldham, Warren J.; Selby, Hugh D. (2016). "Measurements of extinct fission products in nuclear bomb debris: Determination of the yield of the Trinity nuclear test 70 y later". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (29): 8104–8108.