Image

A resident of Alamogordo, who worked at Alamogordo New Mexico’s Holloman Air Force Base, made history in the U.S. space program and history for travel at a speed faster than a .45-caliber bullet in an experiment to test the limits of human endurance.

That same Alamogordo resident was known as the "fastest man on Earth" during the research phase of the US space program to the moon. He accelerated in five seconds from a standstill to 632 m.p.h. The New York Herald Tribune called this Alamogordo resident "a gentleman who can stop on a dime and give you 10 cents change."

He won what will perhaps be even more lasting fame in a test five years earlier, when he suffered injuries owing to a mistake by a US Airforce Captain Murphy. The result was the phrase “Murphy's Law.”

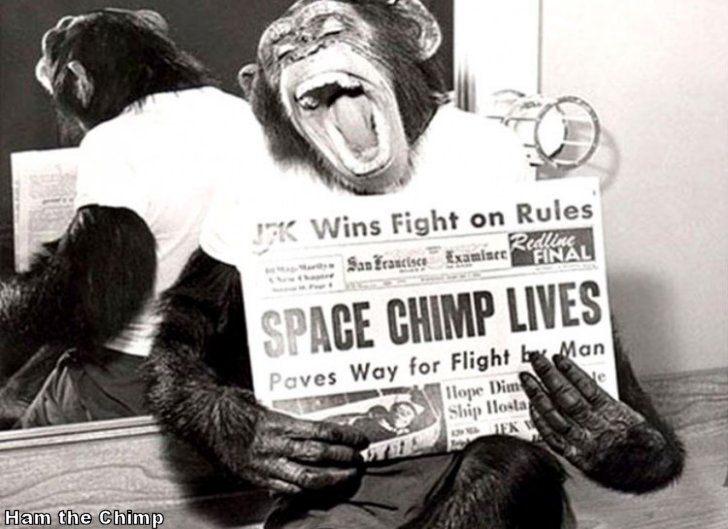

Who was this remarkable Alamogordo resident? Seven years before the US sent the other famous Alamogordo resident Ham, (the three-year-old chimpanzee) into space aboard the Mercury Capsule Number 5, this Alamogordo resident, was himself a live monkey, in many speed and endurance tests that tested the limits of man verses speed and gravity.

This individual of remarkable endurance was John Paul Stapp. Dr. Stapp was a flight surgeon in the U.S. Army Air Forces at the end of World War II, continued in the field of aviation medicine after the war, and transferred to the U.S. Air Force when it was established in 1947, to continue his work on the human response to flight.

Air Force Photo Alamogordo Town News

Air Force Photo Alamogordo Town NewsHis interests from the beginning were in the limits of the human body, when subjected to the increasing forces provided by faster and faster aircraft. In the early 1950s, no one knew what humans could withstand when it came for g-forces, rapid spins, oxygen deprivation, and exposure to cosmic rays. Stapp began a program of human testing to determine those limits, becoming chief of the Aeromedical Field Laboratory at Holloman Air Force Base, New Mexico and living in Alamogordo.

Dr. Stapp made history aboard the Sonic Wind I rocket sled on December 10, 1954, when he set a land speed record of 632 mph in five seconds, subjecting him to 20 Gs of force during acceleration.

Although he had many individuals, available from a group of volunteers for this dangerous test ride, Dr. Stapp chose himself for the mission. He claimed he did not want to place another person into such a potentially hazardous position.

When the sled stopped in just 1.4 seconds, Dr. Stapp was hit with a force equivalent to 46.2 Gs, more than anyone had yet endured voluntarily on the planet to that point. He set a speed record and was a man of much scientific study. Upon ending the ride, he managed half a smile, as he was pulled from the sled. Dr. Stapp was in significant pain, and his eyes flooded with blood from the bursting of almost all of capillaries in his eyes. As Dr. Stapp was rushed to the hospital, his aids, doctors, scientist and he all worried that one or both of his retinas had detached, leaving him blind. Thanks to a studious medical team ready with treatment on the standby, by the next day, he had regained enough of his normal vision to be released by his doctors. His eyesight would never fully recover back to the status prior to the tests but he felt the test was well worth the risk and was happy that he did it verses sending one of the volunteers due to the risk. A less strong man might not have survived the test intact.

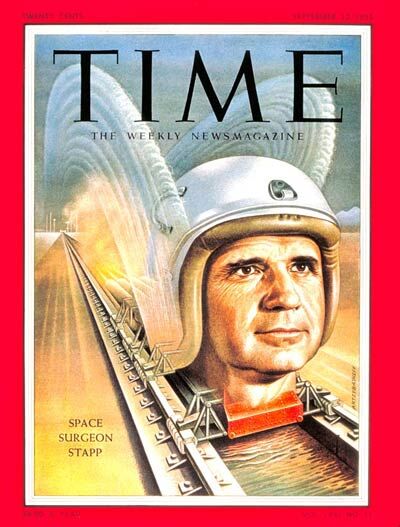

Acclaimed by the world press as “The Fastest Man on Earth,” Dr. Stapp became an international sensation, appearing on magazine covers, television, and as the subject of an episode of “This is Your Life!” He appeared on the cover of Time Magazine…

1954 Time Magazine Cover of Dr. Stapp (Alamogordo Town News with permission)

1954 Time Magazine Cover of Dr. Stapp (Alamogordo Town News with permission)Dr. Stapp was a modest man, in person and was approachable. He lived in Alamogordo after leaving the Air Force and till the end of his life. He used his public acclaim not for personal gain but to pursue his dream of improving automobile safety. As a proponent for public safety, he felt that the safety measures he and his teams were developing for military aircraft should also be used for civilian automobiles.

Dr. Stapp understood the power of celebrity. As such he used his celebrity status to push for the installation of seat belts in American cars. He understood how to politic, navigate the government bureaucracy and use his public persona to push the Department of Transportation to review and eventually implement many now standard safety features. The success of his campaign efforts for public safety is measured in thousands of lives saved and injuries lessened every year by the safety precautions he championed during his lifetime not only in the US but around the world as his measures were adopted as standard world-wide.

Every day when you start your automobile in Alamogordo, Manhattan, Tokyo and beyond we can thank Dr. Stapp for the seatbelts and other safety features that keep us safe as we go onto the roadways.

In those early years of the mid 1950’s Dr. Stapp had hoped to make more runs on the Sonic Wind, with a goal of surpassing 1000 mph, however in June 1956, the sled flew off its track during an unmanned run and was severely damaged beyond appropriate repair.

Dr. Stapp would later ride an air-powered sled known as the “Daisy Track” at Holloman, but never again would he be subjected to the rigors of rocket-powered travel.

Dr. Stapp as an Airforce Colonel next planned and directed the Man-High Project, three manned high-altitude balloon flights to test human endurance at the edge of space. Conducted in June and August 1957, the project’s highlight was the second mission, during which Lieutenant David G. Simons reached an altitude of almost 102,000 feet. Project Man-High was a tremendous scientific success and helped prepare for America’s initial manned space which of course did not happen until after Alamogordo’s other famous resident “Ham” the three-year-old chimpanzee had successfully been launched and returned safely.

Dr. Stapp retired from the Air Force as a colonel in 1970. He went on to become a professor at the University of California’s Safety and Systems Management Center, then a consultant to the Surgeon General and NASA.

He next served as the president of the New Mexico Research Institute in Alamogordo, New Mexico, as well as chairman of the annual “Dr. Stapp International Car Crash Conference.”

In 1991, Stapp received the National Medal of Technology, “for his research on the effects of mechanical force on living tissues leading to safety developments in crash protection technology.” He was also honorary chairman of the Stapp Foundation, underwritten by General Motors to provide scholarships for automotive engineering students.

Dr. Stapp was a well-regarded Alamogordo resident and spoke often at the public high school, in lectures at NMSU Alamogordo and as a guest lecturer at the Space Hall of Fame in Alamogordo. He was always open to talking with young impressionable individuals encouraging the study of science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

Colonel Dr. John Stapp died in Alamogordo on November 13, 1999, at the age of eighty-nine. His many honors and awards included enrollment in the National Aviation Hall of Fame, the Air Force Cheney Award for Valor and the Lovelace Award from NASA for aerospace medical research.

Alamogordo, New Mexico has been called the cradle of America’s space program and offers a museum that applauds our exploration of the heavens with a mix of high-tech entertainment and dramatic exhibits. The United Space Hall of Fame and Space Museum in Alamogordo, New Mexico continues to honor Dr. John P. Stapp naming the Air & Space Park after him. Named after International Space Hall of Fame Inductee and aeromedical pioneer Dr. John P. Stapp, the Air and Space Park consists of large space-related artifacts documenting mankind’s exploration of space. Examples of exhibits include the Sonic Wind I rocket sled ridden by Dr. Stapp and the Little Joe II rocket which tested the Apollo Launch Escape System. At 86 feet tall, Little Joe II is the largest rocket ever launched from New Mexico. Many major breakthroughs in technology occurred in the Alamogordo area, and the museum offers a variety of exhibitions to showcase those milestones. Other features showcased are a tribute to the Delta Clipper Experimental; and the Clyde W. Tombaugh Theater and Planetarium, featuring a giant dome-screen and state-of-the-art surround sound to fully immerse the audience. If in the Alamogordo area or in Southern New Mexico this is a do not miss stop for anyone with an interest in space or the history of space exploration.

New Mexico Museum of Space History

LOCATION: Next to the New Mexico State University, Alamogordo at the Top of NM 2001, Alamogordo, NM

PHONE:(575) 437-2840

HOURS: 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Wednesday through Sunday, closed on Monday and Tuesday

ADMISSION: Adults are $8, Senior/Military/NM Resident $7, Children (4-12) $6, Tots (3 & Under) Free. New Mexico foster families are admitted free. Additional fees for theater and planetarium.

On the Web: www.NMSpaceMuseum.org

Article Author Chris Edwards, Alamogordo Town News, 2nd

Life Media.

Excerpts and Source of Information: New Mexico Museum of Space History, The History Channel, Time Magazine September 12, 1955, The Discovery Channel, "Space Men: They were the first to brave the unknown (Transcript)". American Experience. PBS. March 1, 2016. Retrieved January 2, 2019. "Building 29: Aero Medical Laboratory". Historic Buildings & Sites at Wright-Patterson AFB. United States Air Force. August 12, 2002. Archived from the original on June 22, 2008. Retrieved November 15, 2008. Spark, Nick T. "The Story of John Paul Stapp". The Ejection Site. Stapp JP (August 1948). "Problems of human engineering in regard to sudden declarative forces on man". Mil Surg. 103 (2): 99–102. PMID 18876408. Aviation Week for 3 January 1955 says he accelerated to 632 mph in five seconds and 2800 feet, then coasted for half a second, then slowed to a stop in 1.4 seconds. It says the track was 3500 feet long. Spark, Nick T. (2006). "Whatever Can Go Wrong, Will Go Wrong": A History of Murphy's Law. Periscope Film. ISBN 9780978638894. OCLC 80015522