Image

A note to local elected officials and state lawmakers around the nation, the United States Supreme Court clarified the rules of engagement on social media between the public and elected officials on what’s public and what’s private speech by public officials.

The Supreme Court ruled Friday that members of the public in some circumstances can sue public officials for blocking them on social media platforms, deciding a pair of cases against the backdrop of former President Donald Trump’s contentious and colorful use of Twitter.

The court ruled unanimously that officials can be deemed "state actors" when making use of social media and can therefore face litigation if they block or mute a member of the public.

In two cases before the justices, the Justices ruled that disputes involving a school board member in Southern California and a city manager in Michigan should be sent back to lower courts for the new legal test to be applied.

In a ruling written by Justice Amy Coney Barrett, the court acknowledged that it "can be difficult to tell whether the speech is official or private" because of how social media accounts are used.

The court held that conduct on social media can be viewed as a state action when the official in question "possessed actual authority to speak on the state's behalf" and "purported to exercise that authority."

While the officials in both cases have low profiles, the ruling will apply to all public officials who use social media to engage with the public.

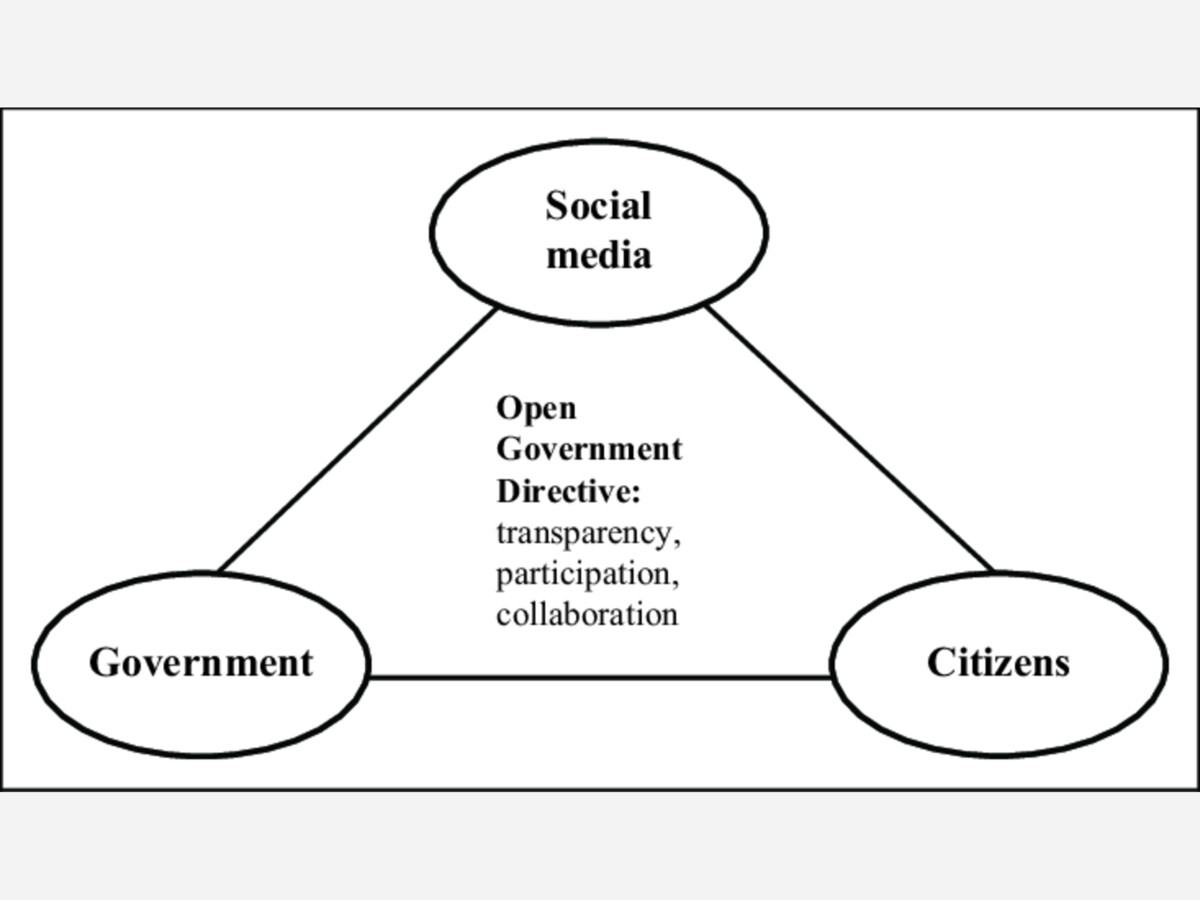

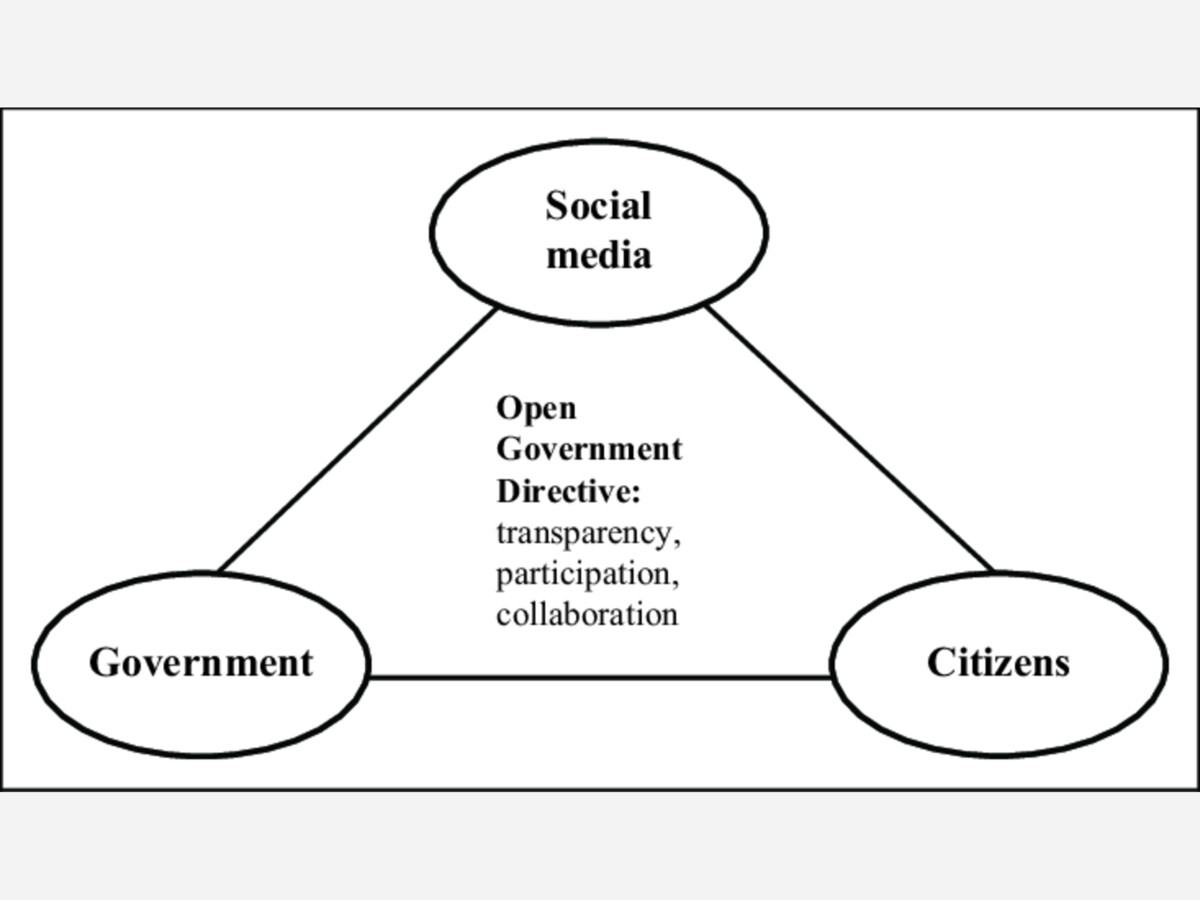

In cities, towns, and villages across the nation, local elected officials and city staff often rely upon social media platforms both as a formal municipal means of communication as well as an informal way to engage with constituents and personal connections. This court decision allows local leaders to move forward with some clarity as to when the First Amendment applies to their social media accounts.

Public officials may use labels and disclaimers on their social media pages, such as “this is the personal page” of the individual or “the views expressed are strictly my own,” which, according to the Court, would entitle the official to “a heavy (though not irrebuttable) presumption that all of the posts on his page were personal.”

However, the Court noted such a disclaimer cannot provide cover to conduct government business on a personal page such as by live streaming a council meeting only on that “personal” page.

The Court notes that the line between private and state action can be “difficult to draw.” The difficulty is magnified, the Court explains, because of the nature of some public officials’ work, which can make it seem like “they are always on the clock.” But the Court emphasized that public officials have their own First Amendment rights, including rights to speak about their employment, that they do not relinquish simply by becoming public officials. The burden is on the plaintiff to show the official is “purporting to exercise state authority in specific posts.” Additional factors, such as the use of governmental staff and resources, may help demonstrate the use of that authority.

The Court explains that its test is derived from the text of Section 1983, which provides a cause of action where “[e]very person who, under color of any statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage, of any State deprives someone of a federal constitutional or statutory right. Thus, a public official has the authority to speak on behalf of the government if based on a written law, regulation, or ordinance that authorizes that person to make official announcements or if there is a well-established custom such that the “power to do so has become permanent and well settled.” The Court notes in situations where an account belongs to the government or is passed down to the occupier of the particular office, and those would be government accounts subject to the First Amendment.

The Local Government Legal Center filed an amicus brief advocating for a clear and easy to apply state action test focused on authority.

But in another case on social media argued on Monday the ruling will come out by June. In that case the Supreme Court on Monday appeared wary of limiting the Biden administration's contacts with social media platforms in a closely watched dispute that tests how much the government can pressure social media companies to remove content before crossing a constitutional line from persuasion into coercion.

The case, known as Murthy v. Missouri, arose out of efforts during the early months of the Biden administration to push social media platforms to take down posts that officials said spread falsehoods about the pandemic and the 2020 presidential election.

The legal battle is one of five that the Supreme Court is considering this term that stand at the intersection of the First Amendment's free speech protections and social media. It was also the first of two that the justices heard Monday that involves alleged jawboning, or informal pressure by the government on an intermediary to take certain actions that will suppress speech.

"It's treating Facebook and these other platforms like they're subordinates," Alito said. "Would you do that to the New York Times or the Wall Street Journal or the Associated Press or any other big newspaper or wire service?" That’s one of the questions of the day can elected officials treat social media platforms and smaller independent news organizations with less respect in policy than they would the large media corporations?

Decisions from the Supreme Court in both cases are expected by the end of June.