Image

Alamogordo, NM – In conservative strongholds like Otero County and across New Mexico, the Second Amendment is often invoked as an absolute command: “the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” Far-right advocates, Republican lawmakers, and groups like the National Rifle Association champion this language to oppose almost any new restriction on gun ownership, framing them as tyrannical overreach. Yet this principled absolutism rarely extends to the federal ban on felons possessing firearms—a 20th-century policy that critics say originated in part to disarm people of color and immigrants, and one that local Republican leaders, including New Mexico Republican Party Chair Amy Barela, have shown little courage to challenge or reform.

The Second Amendment’s text contains no carve-outs for felons, nonviolent offenders, or any other group. Early American gun laws were generally permissive for free white men, often mandating militia service with arms. Restrictions targeted enslaved Black people, Native Americans, and sometimes free Black individuals to preserve racial hierarchies. Post-Civil War Black Codes in the South explicitly barred freed Black people from owning guns to suppress resistance. Northern states introduced discretionary handgun permitting (e.g., New York’s 1911 Sullivan Act) that enabled denial to immigrants, racial minorities, and the poor. In the South, concealed-carry bans and limits on cheap handguns were openly used to disarm Black laborers; a 1941 Florida Supreme Court opinion admitted such a law “was never intended to be applied to the white population.”

The federal felon-in-possession prohibition took shape in the 20th century. The 1938 Federal Firearms Act barred violent felons from receiving interstate-shipped guns. Broader coverage for most felonies (crimes punishable by over one year) came via 1961 amendments and the Gun Control Act of 1968, enacted amid civil rights unrest and assassinations. California’s 1967 Mulford Act—banning loaded public carry and backed by then-Gov. Ronald Reagan and the NRA—illustrates how gun control was sometimes deployed against armed Black activism, specifically the Black Panthers.

These laws now disproportionately impact communities of color due to systemic disparities in the justice system. Black Americans represent about 13% of the population but over 30% of federal felon-in-possession convictions, many from nonviolent drug offenses tied to the racially skewed War on Drugs. Restoration is difficult, often requiring a pardon.

In New Mexico, the contrast is stark. Otero County declared itself a Second Amendment Sanctuary in 2019, resisting state restrictions. Permitless concealed carry has been in place since 2023, and Republican leaders frequently decry gun control as unconstitutional. Yet there is virtually no record of prominent local or state Republicans— including Chair Amy Barela—advocating for meaningful restoration of firearm rights to nonviolent felons after sentence completion. State law bars felons from possessing guns for 10 years post-sentence (restorable only by gubernatorial pardon), and recent GOP-backed bills (e.g., HB49 in 2026) have aimed to stiffen penalties for felons in possession without differentiating violent from nonviolent cases. Barela and other Republican voices have been outspoken on defending gun rights against bills like SB 17, but they have not publicly addressed or pushed to reform the felon ban, even as federal courts increasingly scrutinize its application to nonviolent offenders post-Bruen (2022).

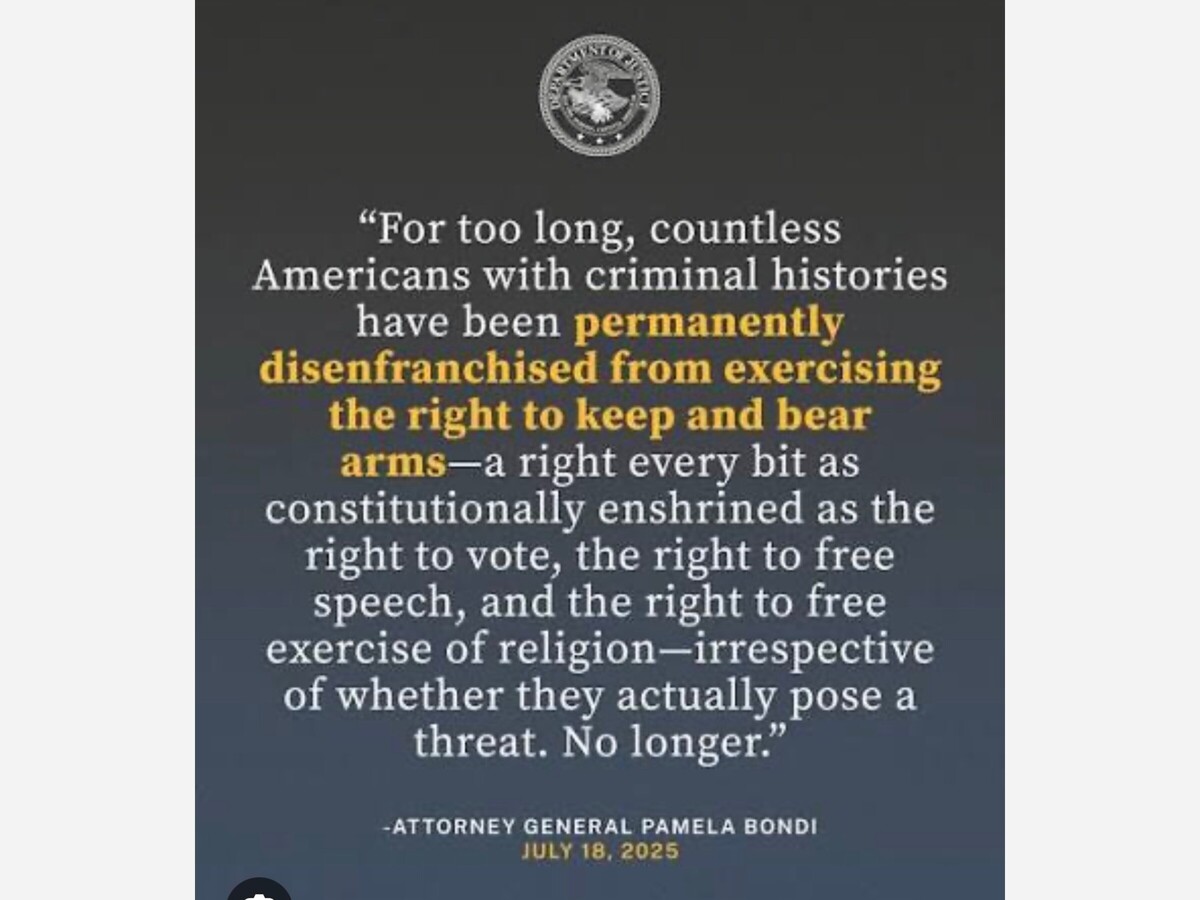

This silence stands in contrast to recent federal developments. On July 18, 2025, the U.S. Department of Justice under Attorney General Pam Bondi published a proposed rule to revive and expand the relief process under 18 U.S.C. § 925(c), allowing certain individuals precluded from possessing firearms due to convictions to petition for restoration—provided they are not likely to act dangerously to public safety. The rule excludes violent felons, registered sex offenders, and illegal aliens but offers a case-by-case pathway for nonviolent offenders. Bondi stated: “For too long, countless Americans with criminal histories have been permanently disenfranchised from exercising the right to keep and bear arms—a right every bit as constitutionally enshrined as the right to vote, the right to free speech, and the right to free exercise of religion—irrespective of whether they actually pose a threat. No longer.” The proposal aligns with President Trump’s emphasis on Second Amendment support and invites public comment.

Despite this federal shift toward addressing permanent disarmament for nonviolent individuals, local far-right leaders in New Mexico have not echoed Bondi’s narrative or shown willingness to confront the issue head-on. Critics argue this reveals a core hypocrisy: the Second Amendment is treated as near-absolute for law-abiding (often white, rural, or conservative) citizens, while policies with historical roots in racial control are accepted or ignored as “common-sense” safety measures. Post-Bruen challenges continue to question whether blanket felon bans fit the nation’s “text, history, and tradition,” and some courts have struck down applications to nonviolent cases.

Until Republican leaders like Amy Barela, John Block and others consistently apply their “shall not be infringed” principle to rehabilitated nonviolent felons—rather than remaining silent or supportive of prolonged restrictions—the selective defense of gun rights will fuel accusations of inconsistency and show nothing but hypocrisy. American gun law history shows the right to bear arms has never been truly universal and has been steeped in racism, acknowledging and addressing that legacy could either unify or further divide the debate.

Note: Author and Journalist Chris Edwards takes a pure constitutionalist view to first and second amendment rights as an advocate for rehabilitative rights and a free press based upon the original tenets of the US Constitution.

Citations

1. District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570 (2008).

2. Ruben, J. D. (2021). “The Racist Roots of Gun Control.” Harvard Law Review Forum.

3. U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. History of Federal Firearms Laws.

4. Cottrol, R. J., & Diamond, R. T. (1991). “The Second Amendment: Toward an Afro-Americanist Reconsideration.” Georgetown Law Journal.

5. Spitzer, R. J. (2020). The Politics of Gun Control. Routledge.

6. Florida Supreme Court, Watson v. Stone (1941).

7. Mulford Act (California Penal Code §§ 12031, 25850 et seq., 1967).

8. Gun Control Act of 1968, Pub. L. 90-618.

9. New York Sullivan Act (1911).

10. Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. 393 (1857).

11. Various historical accounts from Southern Black Codes (1865–1866).

12. Simon, J. (2007). Governing Through Crime. Oxford University Press.

13. Winkler, A. (2011). Gunfight: The Battle over the Right to Bear Arms in America. W.W. Norton.

14. Coates, T-N. (2013). “The Case for Reparations.” The Atlantic (discussing racial aspects of gun control history).

15. Bogus, C. T. (2008). “The Hidden History of the Second Amendment.” University of California Davis Law Review.

16. U.S. Sentencing Commission data on federal felon-in-possession cases (2020–2024).

17. New Mexico statutes: N.M. Stat. Ann. § 30-7-16 (felon firearm prohibition).

18. Collateral Consequences Resource Center – Restoration of Rights Project (New Mexico profile).

19. U.S. Department of Justice Press Release (July 18, 2025): “Justice Department Publishes Proposed Rule to Grant Relief to Certain Individuals Precluded from Possessing Firearms.”

20. Bondi, P. (2025). Quote from DOJ press release on restoration of Second Amendment rights.