Image

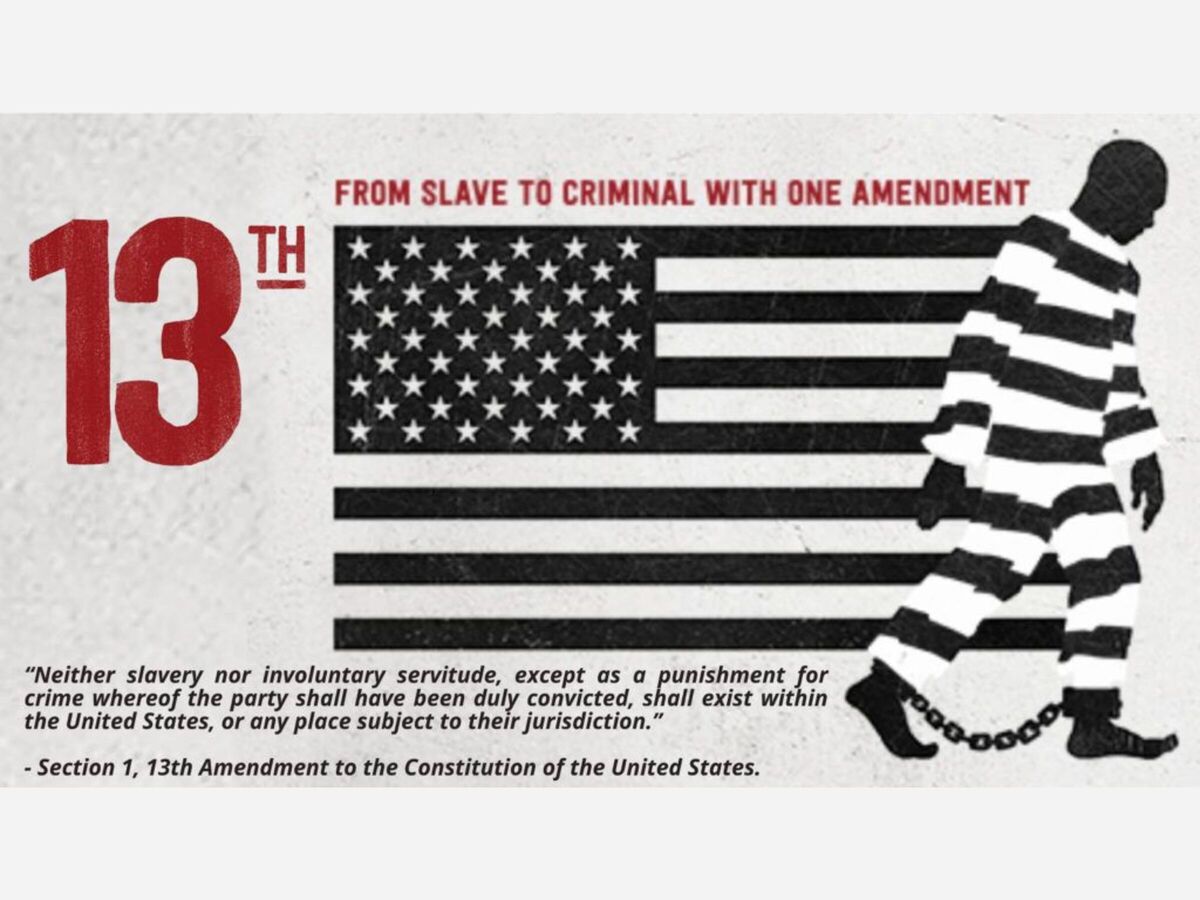

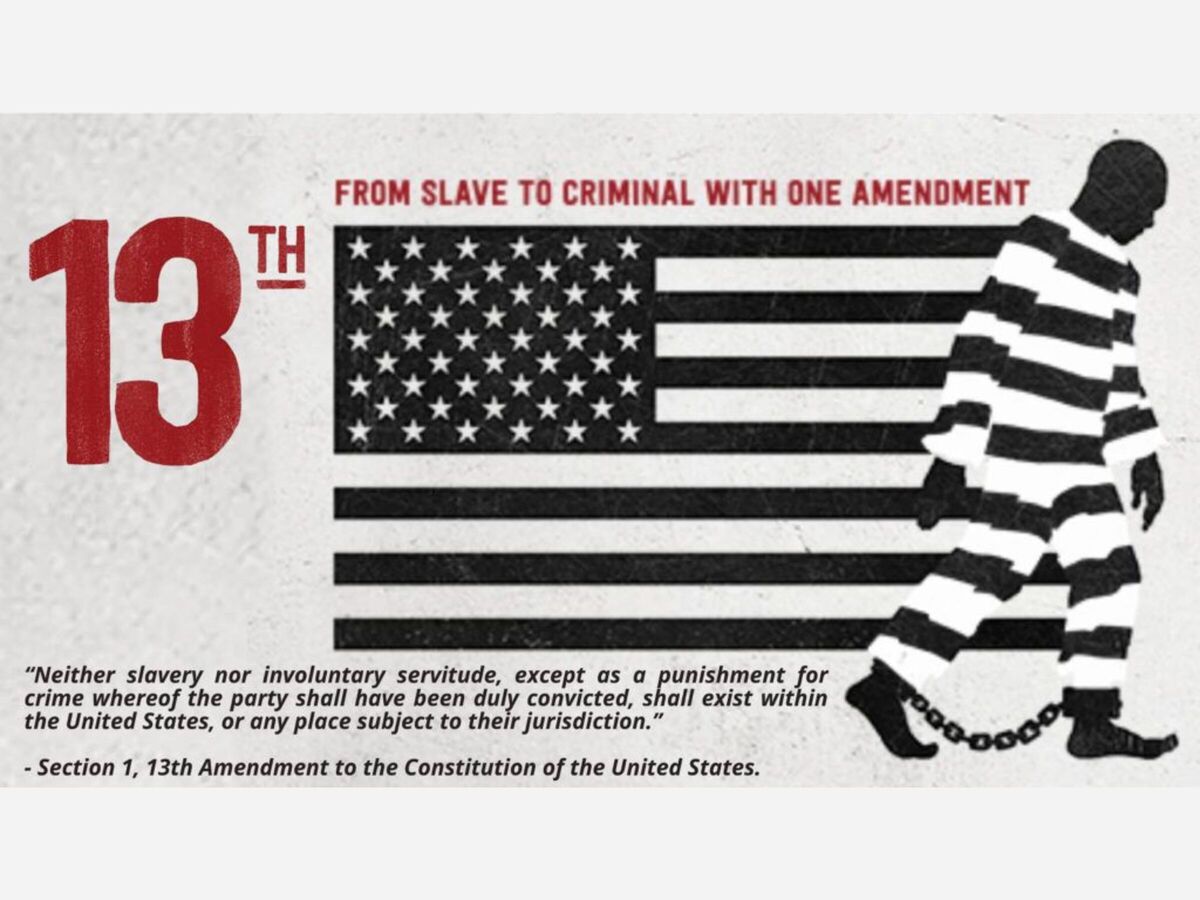

With the recent focus on Juneteenth, the public is familiarizing themselves with the 13th Amendment to the US Constitution. What is recognized and we were all taught in civics classes is that the amendment abolished slavery and involuntary servitude. That at face value is true and 2 years after passage all states recognized that thus the Juneteenth celebrations.

What we were not taught in history class or civics was the loophole. In reading this article, you will learn history but also how that loophole benefits for-profit prisons but harms counties where they are located. The reader will learn, good paying jobs promised to the public are not created in the local community due to the loophole creating exploitations and ultimately harming local communities like Otero County and Alamogordo, robbing the community of those promised good paying jobs for the local citizens.

Few of us neither realized the amendment has a loophole nor paid it attention! A big loophole, that has allowed for exploitation, that few realize that still exists today…

The amendment reads:

Thirteenth Amendment

Section 1

Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Section 2

Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

The Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime. The amendment was passed by Congress on January 31, 1865, and ratified by the required 27 of the then 36 states on December 6, 1865, and proclaimed on December 18.

“It is said that no one truly knows a nation until one has been inside its jails. A nation should not be judged by how it treats its highest citizens, but its lowest ones. - Nelson Mandela

The passage of the 13th Amendment was seen as a successful move to migrate the nation away from slavery. But southern business owners sought to reproduce the profitable arrangement of slavery with a system called peonage, in which disproportionately black workers were entrapped by loans and compelled to work indefinitely due to the resulting debt.

Peonage continued well through Reconstruction and ensnared a large proportion of black workers in the South and harmed wealth generation of black workers of which the repercussions of generational wealth loss are felt today.

These workers remained destitute and persecuted, forced to work dangerous jobs, and further confined legally by the racist Jim Crow laws that governed the South. Peonage differed from chattel slavery because it was not strictly hereditary and did not allow the sale of people in the same fashion. However, a person's debt—and by extension a person—could still be sold, and the system resembled antebellum slavery in many ways.

With the Peonage Act of 1867, Congress abolished "the holding of any person to service or labor under the system known as peonage", specifically banning "the voluntary or involuntary service or labor of any persons as peons, in liquidation of any debt or obligation, or otherwise." However, forms of it persisted especially in the deep south until the 1940’s.

In 1939, the Department of Justice created the Civil Rights Section, which focused primarily on First Amendment and labor rights. The increasing scrutiny of totalitarianism in the lead-up to World War II brought increased attention to issues of slavery and involuntary servitude, abroad and at home. The U.S. sought to counter foreign propaganda and increase its credibility on the race issue by combatting the Southern peonage system. Under the leadership of Attorney General Francis Biddle, the Civil Rights Section invoked the constitutional amendments and legislation of the Reconstruction Era as the basis for its actions.

In 1947, the DOJ successfully prosecuted Elizabeth Ingalls for keeping domestic servant Dora L. Jones in conditions of slavery. The court found that Jones "was a person wholly subject to the will of defendant; that she was one who had no freedom of action and whose person and services were wholly under the control of defendant and who was in a state of enforced compulsory service to the defendant." The Thirteenth Amendment enjoyed a swell of attention during this period, but from Brown v. Board of Education (1954) until Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co. (1968) it was again eclipsed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868, has generated more lawsuits than any other provision of the U.S. Constitution. Section 1 of the amendment has been the centerpiece of most of this litigation. It makes "All persons born or naturalized in the United States "citizens of the United States and citizens of the state in which they reside. This section also prohibits state governments from denying persons within their jurisdiction the privileges or immunities of U.S. citizenship, and guarantees to every such person due process and equal protection of the laws. The Supreme Court has ruled that any state law that abridges Freedom of Speech, freedom of religion, the right to trial by jury, the Right to Counsel, the right against Self-Incrimination, the right against unreasonable searches and seizures, or the right against cruel and unusual punishments will be invalidated under section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment. This holding is called the Incorporation Doctrine.

However back to the 13th amendment and the concern of the exemption for penal labor from its prohibition of forced labor. This amendment allows prisoners who have been convicted of crimes (not those merely awaiting trial) to be required to perform labor or else face punishment while in custody. While on the surface that makes sense and does not sound like a bad thing, we must keep in mind this amendment was passed well before the idea of privatized for profit corporate run prisons.

Prison labor, or penal labor, is work that is performed by incarcerated and detained people. Not all prison labor is forced labor, but the setting involves unique modern slavery risks because of its inherent power imbalance and because those incarcerated have few avenues to challenge abuses behind bars. Free prison labor, or work that is performed voluntarily, can be a valuable activity but it becomes exploitative when there are elements of coercion, force, and threat of punishment against detainees.

The line between free prison labor and forced prison labor is difficult to define. The International Labor Organization (ILO) lists several indicators of free prison labor which, if absent, could point to conditions of modern slavery. These include the right to written consent forms, wages and working hours comparable to those of free workers, and standard health and safety measures. The ILO states that these factors must be considered “as a whole” to determine if prison labor is forced.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) discusses prison labor in its so-called Nelson Mandela Rules, which outline minimum standards by which to treat those incarcerated; rule 97 states that those incarcerated “shall not be held in slavery of servitude” and that they must be covered by the same wage, health, and safety standards as free citizens. That is very much different that the US 13th Amendment to the Constitution.

The United States, which has the world’s largest prison population, aimed to abolish slavery with the Thirteenth Amendment of 1865. But the Thirteenth Amendment echoes the ILO’s definition by allowing involuntary servitude—in the form of forced labor— “as punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

Meanwhile, American labor laws such as the Fair Labor Standards Act exclude those incarcerated by classifying their working relationship as penal, not economic.

Incarcerated people are thus unprotected from forced labor. Activists have further pointed out that mass incarceration and racial profiling in the United States has led to African Americans being incarcerated at far higher rates than their white counterparts. With forced labor remaining legal as punishment for a crime, the legacy of slavery and racism persists in the U.S. industrial prison complex. In fact, organizers of a 2018 prison strike called their labor exploitation “prison slavery,” with those incarcerated being farmed out to local governments and companies to perform labor for just pennies a day.

The U.S. is one of several countries around the world where mass incarceration has in effect become an avenue for forced labor based with clear links to racial discrimination. Commentators have called the exemption of prison labor a “fatal flaw” in the 13th Amendment; indeed, almost immediately after its passing, states began to take advantage of it to continue to exploit black and brown communities. The practice continues to this day, with many major corporations complicit in using free, cheap, or exploitative prison labor in what has come to be known as the prison-industrial system.

As recently as this year and as close as El Paso we see where this labor is exploited to do jobs others will not do or do not want to do.

The El Paso Times reported: Low-level inmates from El Paso County detention facility work while moving bodies wrapped in plastic at one of ten refrigerated temporary morgue trailers in a parking lot of the El Paso County Medical Examiner's office on November 16, 2020, in El Paso, Texas. The inmates, who are also known as trustees, are volunteering for the work and earn $2 per hour amid a surge of COVID-19 cases in El Paso. Texas surpassed 20,000 confirmed coronavirus deaths today, the second highest in the U.S., with active cases in El Paso now well over 30,000.

The recent surge in labor performed in prison has led to more people laboring in captivity than were enslaved 200 years ago. The surplus value that is created by the labor of prisoners takes a system that theoretically exists to protect society and turns it into one that steals the work of individuals and lowers the market value of all labor.

However, in the late 1960s and 1970s, the government increased its criminalization of dissent in America, which caused the skyrocketing of incarceration rates. Richard Nixon started his war on drugs, which was first used to crack down on Black activists. This led into the Reagan administration increasing the penalties for the possession of crack cocaine and other narcotics. Then in 1994, the Clinton Crime bill, championed by Joe Biden, resulted in the largest increase of incarcerated people in the history of the United States.

During this surge in mass incarceration, state and federal governments also started loosening the restrictions set in the 1920s and 1930s on private corporations using prison labor through the Private Industry Enhancement Certification Program (PIECP), which was authorized by Congress in 1979. This program. which allows private industries to form partnerships with prisons to use inmate labor, is supposed to follow certain requirements, including paying a prevailing wage. However, wages under the PIECP program have been reported to be as low as 0.16 cents a day.

Over 4100 corporations use the PIECP program to profit from prison labor made available by mass incarceration. 385 of these are publicly traded, and include companies such as 3M, ACE Hardware, Amazon, Microsoft, and Northrop Grumman.

The connection between prison labor and racial discrimination is also clear in immigration detention. Immigration detainees are at particular risk of modern slavery; according to the International Detention Coalition, immigration detention tends to have extraordinarily little oversight and is “among the opaquest areas of public administration” worldwide. This lack of oversight allows for widespread human rights abuses against immigration detainees—including forced labor.

In the United States, immigration detainees, including refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants, are especially vulnerable because they are often held by private prisons. Whereas over 90 percent of the American prison population is held in state-run facilities, more than 70 percent of people in immigration detention are held in private detention centers.

Because they are for-profit and receive a fixed income from the government, these facilities are incentivized to cut costs and rely on detainees for much of their operation—paying them as little as a dollar a day.

Freedom United an organization that is fighting to change the 13th Amendment and is currently campaigning against Core Civic—the second-largest private prison and immigration detention company in the United States—which has been the target of several lawsuits for subjecting detainees who have not been charged with any crimes to forced labor, sometimes even under the threat of being sent to solitary confinement.

Per The Case Against Private Detention Facilities in New Mexico, Authors: Margaret Brown Vega, Lynne Canning, Nathan Craig, and Else Droof with contributions by Sarah Manges October 2020

In the 1990s, New Mexico witnessed one of the nation's biggest surges in the use of private prisons, a national trend for which New Mexico was an epicenter. Privatization was intended to address overcrowding and poor conditions and accelerated when the State of New Mexico began to view private prisons as a development tool in rural areas. In New Mexico, the shift to private prisons came on the heels of the state’s worst prison riot, and one of the worst in the nation. Evidence of corruption in the state prison system, promises of reform, and cost cutting fed the private prison building boom.3

Additionally, the new facilities were built under the untested pretext that rural prison hosting would drive economic growth and create jobs. The early promises of improved conditions, cost savings, and economic development for New Mexico, however, were not realized by privatization. Department of Justice and Government Accounting Office reports show that private prisons provide almost no cost savings and what meager “savings” are achieved is accomplished by reduced staffing and lower wages both problems that have plagued New Mexico.

Otero County plays host to 2 for profit prisons – The Otero County Prison Facility and The Otero County Processing Center.

A recent study shows that Otero and Cibola counties, the two non-metro counties that host the largest number of private prison beds, do not have significantly lower unemployment rates than adjacent non-metro counties. The presence of multiple large private prisons in these counties objectively produces no meaningful change in unemployment. The majority of those employed at the two Otero County facilities live in El Paso, Texas, not Chaparral or Alamogordo, New Mexico. The employment boom that was promised when facilities such as the ones in Otero were built simply has not materialized.

In Chaparral, New Mexico advocates who visited the Otero County Processing Center spoke to individuals detained at the facility who did heavy landscaping work, laid foundation, and built a shade structure for staff, 20 performed welding, maintained, and repaired the building, and cleaned inside the facility, in addition to cooking, doing laundry, and providing haircuts.

These activities are all performed as part of the work program, in which individuals are paid $1 per day for 8 hours of work. Most if not all these tasks could easily provide much needed work for Chaparral or Alamogordo Otero County residents, but it is difficult for residents to compete with such cost-saving wages paid to detained immigrants.

The risk of incarcerated people facing forced labor is heightened dramatically during times of crisis. Amid the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, state governments in the U.S. have relied on prison labor to produce essential medical supplies, including hand sanitizer and face masks, and stacking bodies as mentioned in El Paso. Those incarcerated face consequences for refusing to participate and typically earn less than a dollar a day, and are at high risk of infection given the low levels of sanitation and overcrowding in American prisons that makes social distancing impossible. The exploitative practices have been decried by critics as “nothing less than slave labor.”

Thus, the impact or repercussions of the 13th Amendment are even felt locally in Alamogordo and Otero County today. Those repercussions of low wage prisoners exploited by for profit prisons and doing many of the jobs that should be offered to local residence of Otero County at a living wage. But instead, what is happening is prisoners are exploited and those jobs in welding, construction and maintenance are not offered to the local citizens of Otero County and the promise of good paying jobs for the locals is lost.

Last week Oregon Sen. Jeff Merkley and Georgia Rep. Nikema Williams reintroduced legislation to close the prison loophole in the 13th Amendment. We challenge the congressional leaders from New Mexico Representatives Yvette Herrell, Melanie Ann Stansbury and Teresa Leger Fernandez to join the effort. We challenge New Mexico’s two Senators to lead the charge on the Senate side of the Legislature.

Why? Because it is the right thing to do, for profit prisons are exploiting the incarcerated.

Why? Because for profit prisons are exploiting the incarcerated and keeping good paying and skilled jobs away from the local citizens of Otero County and other counties in New Mexico for which these jobs should be offered.

Why? Because this is not just about civil rights, or human rights but it is about jobs in the state of New Mexico and throughout the nation that should be offered as livable wage jobs to the public for which these institutions have settled for business operations.

To listen to this story via a podcast or share this story via podcast for those that would rather listen than read, click the link below. Also, please, contact your elected representatives to support prison reform and job creation in your local communities, rather Alamogordo or beyond...

Author Chris Edwards, sourced and quoted content from: MSNBC, US Constitution, Wikipedia, Freedom United, Freedom United Project, The Real News.com, The Case Against Private Detention Facilities in New Mexico, Authors: Margaret Brown Vega, Lynne Canning, Nathan Craig, and Else Droof with contributions by Sarah Manges October 2020. Oxford, Andrew. “New Mexico Trying to Recover $3.6m from Private Prison Company.” News. Santa Fe New Mexican, August 20, 2018. http://www.santafenewmexican.com/news/local_news/new-mexico-trying-to[1…, Julian. “Lawmakers Want Answers from Ice, Contractor Regarding Covid-19 Outbreak at Nm Jail.” Border Report, August 18, 2020. https://www.borderreport.com/hot-topics/migrant-centers/lawmakers-want[…. El Paso Times, Alamogordo News, Prison Legal News

About Chris Edwards author of Removing Barriers to State Occupational Licenses to Enhance Entrepreneurial Job Growth: Out of Prison, Out of Work Paperback, speaks from the point of view of criminal justice reform and there are significant references to the impact on post incarcerated individuals of the existing framework of Occupational Licensing and how reform will assist in job creation. The proposed reforms come from a standpoint of job creation and improving entrepreneurial opportunities within California and beyond. This book is fact based with significant documentation and research and is a personal plea for reform to not only California legislators but those across the nation.

https://www.amazon.com/Removing-Barriers-Occupational-Licenses-Entrepreneurial/dp/1081556544