Image

On January 31, 1961, a three-year-old chimpanzee and resident of Alamogordo New Mexico’s Holloman Air Force based named HAM, made history in the U.S. space program and history for world space travel in Mercury Capsule No. 5.

What is the story of HAM, his connection to Alamogordo New Mexico and how did he become one of the most famous chimps in history?

By the end of January 1961, the technical outlook for Project Mercury America’s Space Program was improving. The end of the qualification flight tests was in sight, if only the Little Joe, Redstone, and Atlas boosters would cooperate. The highest priority at the time was to make sure the Mercury-Redstone combination was prepared for the first manned suborbital flights. Now, according to the plan, the reliability of the system required demonstration by the second Mercury-Redstone (MR-2) flight, with a chimpanzee aboard, as a final check to man-rate the capsule and launch vehicle.

Preparations for the MR-2 mission with a chimpanzee aboard had begun long before the actual flight. Between manufacturing the capsule and flight readiness certification, many months of testing and reworking were all necessary at the McDonnell plant, at Marshall Space Flight Center, and at Cape Canaveral.

Capsule No. 5, designated for the MR-2 flight, had been near the end of its manufacturing phase in May 1960. When it was completed, inspectors from the Navy Bureau of Weapons stationed at St. Louis, in cooperation with STG's liaison personnel at McDonnell, watched it go through a specified series of tests, and the contractor corrected all detected deficiencies.

After capsule systems tests and factory acceptance tests, capsule No. 5 was loaded into an Air Force cargo plane and shipped to Marshall Space Flight Center. In Huntsville, Alabama Wernher von Braun's team hurried through its checkouts of the compatibility of capsule No. 5 with Redstone booster No.2.

On October 11, 1960, the capsule arrived by air at the Cape, where the first checkout inspections, under the direction of F. M. Crichton, uncovered more discrepancies, raising to 150 the total of minor rework jobs to be done. Because of the complexities of the stacked and interlaced seven miles of wiring and plumbing systems in the Mercury capsule, however, each minor discrepancy became a major cost in the time necessary for its correction.

Capsule No. 5 contained several significant innovations. There were five new systems or components that had not been qualified in previous flights: the environmental control system, the attitude stabilization control system, the live retrorockets, the voice communications system, and the "closed loop" abort sensing system. Capsule No. 5 also was the first in the flight series to be fitted with a pneumatic landing bag. This plasticized fabric, accordion-like device was attached to the heatshield and the lower pressure bulkhead; after reentry and before landing the heatshield and porous bag were to drop down about four feet, filling with air to help cushion the impact. Once in the water, the bag and heatshield should act as a sort of sea anchor, helping the spacecraft to remain upright in the water.

On big fear from space travel was heat at re-entry. Since the anticipated re-entry temperature would reach 1000 degrees F. Temperatures on the conical portion of the spacecraft might approach 250 to 300 degrees F, but, compared with about 1,000 to 2,000 degrees for an orbital mission, the ballistic flights should be cool in comparison. But can a living soul be protected from those high levels of heat?

And here steps in HAM, our historic Chimpanzee. Publicity once again focused on the biological subject in the MR-2 experiment. The living being chosen to validate the environmental control system before committing a man to flight was a trained chimpanzee about 44 months old. Intelligent and normally docile, the chimpanzee is a primate of sufficient size and sapience to provide a reasonable facsimile of human behavior. Its average response time to a given physical stimulus is .7 of a second, compared with man's average .5 second. Having the same organ placement and internal suspension as man, plus a long medical research background, the chimpanzee chosen to ride the Redstone and perform a lever-pulling chore throughout the mission should not only test out the life-support systems but prove that levers could be pulled during launch, weightlessness, and re-entry.

A colony of chimpanzees including Ham were key to mission success. Ham's name is an acronym for the laboratory that prepared him for his historic mission—the Holloman Aerospace Medical Center, located at Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico, southwest of Alamogordo. His name was also in honor of the commander of Holloman Aeromedical Laboratory, Lieutenant Colonel Hamilton "Ham" Blackshear.

Ham was born in July 1957 in French Cameroon (now Cameroon), captured by animal trappers and sent to Rare Bird Farm in Miami, Florida. He was purchased by the United States Air Force and brought to Holloman Air Force Base in July 1959. There were originally 40 chimpanzee flight candidates at Holloman. After evaluation, the number of candidates was reduced to 18, then to six, including Ham. Officially, Ham was known as No. 65 before his flight, and only renamed "Ham" upon his successful return to Earth. This was reportedly because officials did not want the bad press that would come from the death of a "named" chimpanzee if the mission were a failure. Among his handlers, No. 65 had been known as "Chop Chop Chang."

Beginning in July 1959, the two-year-old chimpanzee was trained under the direction of neuroscientist Joseph V. Brady at Holloman Air Force Base Aero Medical Field Laboratory to do simple, timed tasks in response to electric lights and sounds. During his pre-flight training, Ham was taught to push a lever within five seconds of seeing a flashing blue light; failure to do so resulted in an application of a light electric shock to the soles of his feet, while a correct response earned him a banana pellet.

Ham and the group of "Astro-chimps" were transferred from Holloman as the flight neared and were re-stationed and further trained, in a building behind Hangar S on January 2, 1961. There the animals became acclimatized to the change from the 5,000-feet altitude in New Mexico to their sea level surroundings at the Cape.

Separated into two groups as a precaution against the spread of any contagion among the whole colony, the animals were led through exercises by their handlers.

Mercury capsule mockups were installed in each of the compounds. In these, the animals worked daily at their psychomotor performance tasks. By the third week in January, 29 training sessions had made each of the six chimps a bored but well-fed expert at the job of lever-pulling.

On January 31, 1961, Ham was secured in a Project Mercury mission designated MR-2 and launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida, on a suborbital flight. Ham's vital signs and tasks were monitored by sensors and computers on Earth. The capsule suffered a partial loss of pressure during the flight, but Ham's space suit prevented him from suffering any harm. Ham's lever-pushing performance in space was only a fraction of a second slower than on Earth, demonstrating that tasks could be performed in space. Ham's capsule splashed down in the Atlantic Ocean and was recovered by the USS Donner later that day.

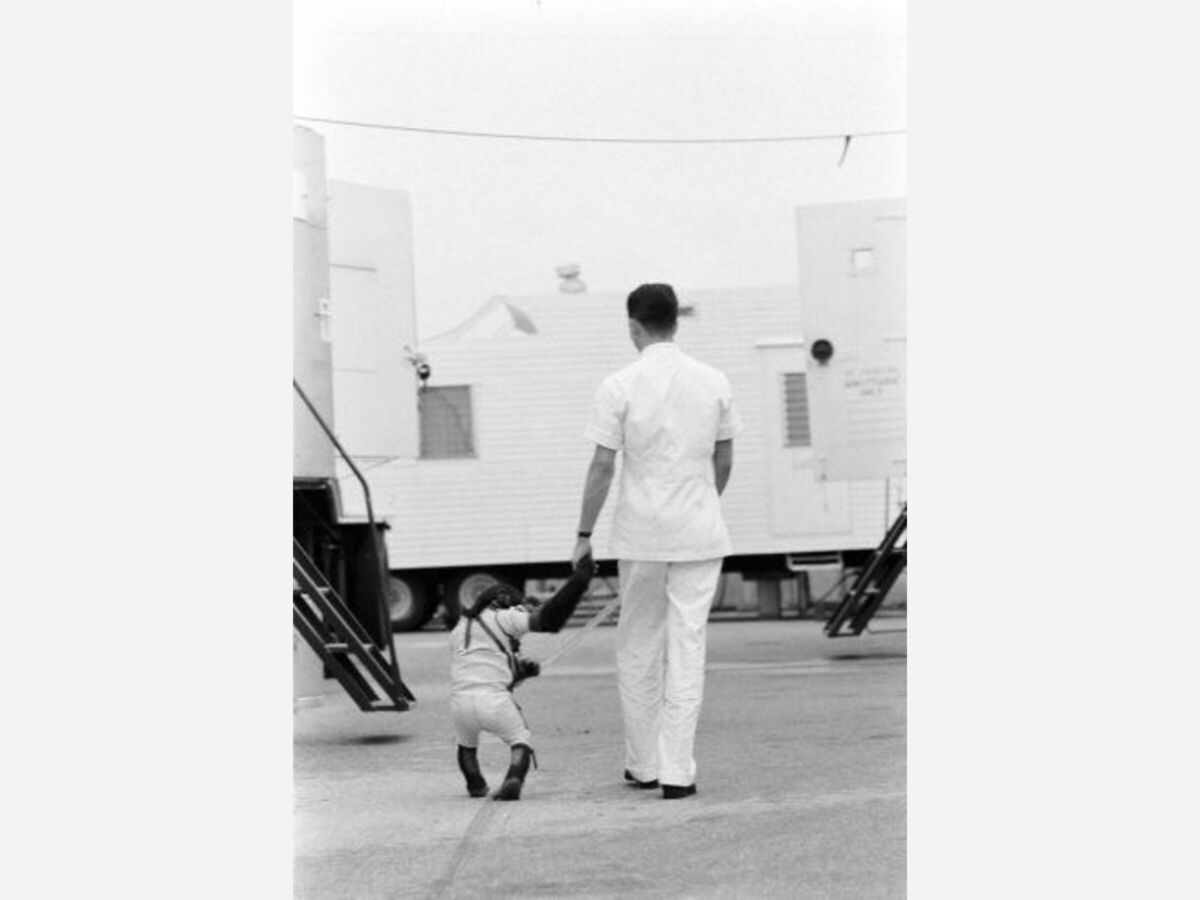

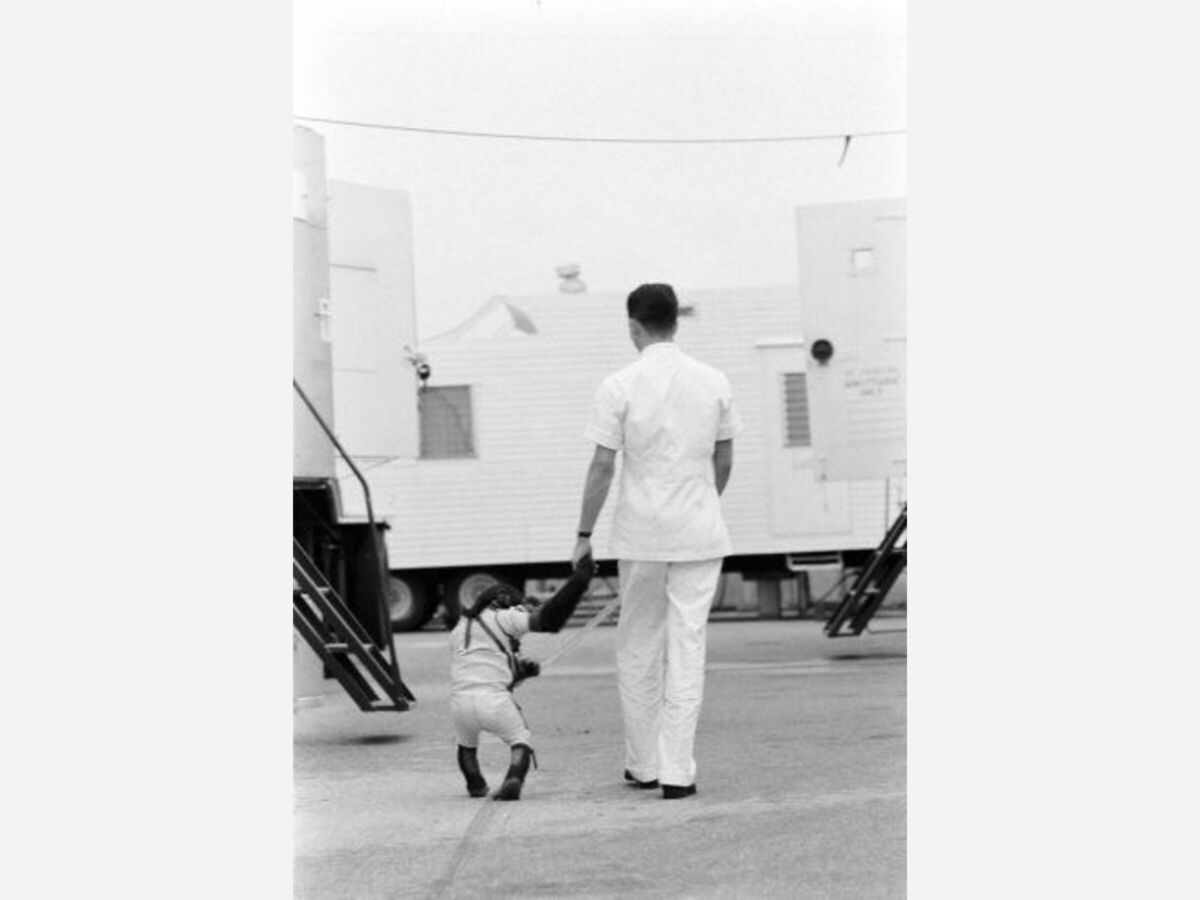

The capsule containing Ham was recovered via splashdown and a "hand-shake" welcome after his flight on a Mercury-Redstone rocket, was his greeting by the commander of the recovery ship, USS Donner.

His only physical injury was a bruised nose. His flight was 16 minutes and 39 seconds long.

The results from his test flight led directly to the mission Alan Shepard made on May 5, 1961, aboard Freedom 7.

The space program continued and of course we eventually did indeed make it to a moon landing.

As for Ham. He eventually retired. On April 5, 1963, Ham was transferred to the National Zoo in Washington, D.C. where he lived for 17 years before joining a small group of captive chimps at North Carolina Zoo on September 25, 1980.

After his death on January 19, 1983, Ham's body was given to the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology for necropsy. Following the necropsy, the plan was to have him stuffed and placed on display at the Smithsonian Institution, following Soviet precedent with pioneering space dogs Belka and Strelka.

However, this plan was abandoned after a negative public reaction. Ham's remains, minus the skeleton, were buried at the International Space Hall of Fame in Alamogordo, New Mexico. Colonel John Stapp gave the eulogy at the memorial service. The skeleton is held in the collection of the National Museum of Health and Medicine. Details of Ham’s story more photos and of course his grave is visible to all to see on the grounds of the International Space Hall of Fame in Alamogordo and is a must see for animal lovers and space and history buffs alike.

In final follow-up to Ham’s story. Ham's backup, Minnie, was the only female chimpanzee trained for the Mercury program. After her role in the Mercury program ended, Minnie became part of an Air Force chimpanzee breeding program, producing nine off-spring and helping to raise the offspring of several other members of the chimpanzee colony. She was the last surviving Astro-chimpanzee and died at age 41 on March 14, 1998.

Mankind owes a debt of gratitude to Ham and to all the pioneering chimps that were part of the NASA space program that lifted man from earth to the stars above.