Image

FARMINGTON — On Oct. 21, 1921, residents in Farmington heard a hissing roar as a natural gas well 10 miles upriver blew skyward — the debut of the first commercial well in the coal-bed formation known as the San Juan Basin. This stream of natural gas would transform northwestern New Mexico from a sleepy agricultural region to a community that triumphantly built itself on fossil fuels.

But in October 2021, exactly one week and 100 years after this first lucky strike, a conference held to commemorate the first century of oil and gas development in the basin was decidedly less triumphant. Speakers at the San Juan Basin Energy Conference talked of a “tumultuous decade” in the basin and of the “worst downturn in the San Juan Basin’s history.”

They had reason to be glum. Since about 2009, fluctuations in gas prices and aging oil and gas well infrastructure have pushed the San Juan Basin into a steep decline. In the past five years, all the major oil and gas companies — ConocoPhillips, BP, ExxonMobil — sold off their assets to focus on the prolific fossil resources in the Permian Basin, at the opposite corner of the state. Their property was snapped up almost entirely by private-equity-backed companies that promised to trim the fat from the major oil companies’ bloated operations and turn a profit from the region’s declining wells.

On stage at the conference, the speakers were deferential to these “low-cost” producers that now own the vast majority of wells in the basin. Conscious of the repercussions of irking a potential customer or investor, politicians and well-service contractors expressed their gratitude for “all of the basin’s operators.” But in private, the people in the San Juan have less congenial things to say.

They talk about the desperate feeling they get when they walk into their town’s empty stores and restaurants, the pit that forms in their stomachs when they talk to their neighbors about their job prospects. They describe an aimlessness and lack of community they hadn’t felt before, and the idea that even as rig counts climb and oil and gas prices skyrocket, the prosperity of the past isn’t coming back.

Although residents’ complaints are diffuse, the vast majority center around a mysterious private company that has made headlines for its high profits and its title as the country’s largest methane emitter, the basin’s largest operator: Hilcorp Energy.

Hilcorp was launched in 1989, founded by former Exxon executive Jeffery Hildebrand, who still serves as chairman of the board.

Unlike the CEOs of many public oil and gas companies, Hildebrand keeps a relatively low profile. He rarely gives interviews or makes statements about the company’s progress. The most media attention Hildebrand gets is for his exploits playing polo on his property in Aspen, Colorado, his reported purchase of John Denver’s adjacent estate and his rapidly ballooning net worth, now estimated at over $12 billion.

In 2017, when Hilcorp bought out the San Juan operations of ConocoPhillips and Exxon affiliate XTO, the company became the basin’s biggest producer overnight. But Hilcorp, like its board chairman, has done little to draw attention to its presence in the Four Corners. Representatives for the company would not comment when approached with questions for this story and multiple phone calls and emails to various Hilcorp employees went unanswered.

While Conoco and its predecessors typically staffed a high-ranking official in New Mexico throughout their years in the basin, Hilcorp executives rarely leave headquarters in Houston. Instead of large, publicly announced donations to local nonprofits and fundraising campaigns, Hilcorp lets each of its employees give $2,500 to a charity of their choice, much of which is not invested in the basin’s local community. Whereas Conoco’s last basin manager received community awards for her service and fundraising, Hilcorp’s name and employees are practically invisible, local residents say.

And Hilcorp isn’t the only obscure name to enter the basin in the past few years. Since 2017, every major oil company has left the San Juan and been replaced by a private company with financing from shadowy private equity firms.

This mass exodus from Big Oil to private oil has had distinctive local impacts in the Four Corners – few of them positive, residents say. But it was also part of a much larger global shift. Instead of trying to own a piece of everything, companies began focusing on basins that provide the highest returns — while turning away from assets that produced higher greenhouse gas emissions.

Between 2017 and 2021, 25 to 30 percent of oil and gas deals worldwide shifted their assets from public companies to private ones, according to research released May 10 by the Environmental Defense Fund. This change of hands has not only raised concerns about transparency; it could also have major implications for the climate. The study found that in many cases these sales shifted oil and gas assets from companies with climate and environmental goals to those without them or with less strict targets.

Older, less productive basins like the San Juan are often the areas ensnared in these deals. Because these aging basins often have outdated equipment, they can have higher greenhouse gas emissions.

“We’ve seen a lot of this turnover in older basins across the country,” said Brad Handler, a researcher in oil and gas finance at the Colorado School of Mines.

In the San Juan Basin, the bout of sales delivered a win-win situation for both sellers and buyers: The big companies got to shed some considerable weight and the smaller companies got to acquire ready-made well infrastructure at a discount.

Companies like Conoco were able to cut spending and focus attention on their higher-producing operations in places like the Permian Basin, while off-loading thousands of wells fitted with antiquated, greenhouse-gas-spewing equipment that had become an environmental liability. ConocoPhillips declined to comment for this story.

Following its $3 billion sale to Hilcorp, Conoco greatly reduced its operating costs. In its annual sustainability report, the company showed a 22 percent decrease in its emissions and announced, to much fanfare from investors, that it would begin to implement strict emissions targets in the future.

But the emissions that Conoco shed from its ledgers didn’t go anywhere.

According to an analysis of Environmental Protection Agency data by the Clean Air Task Force and the nonprofit investor network CERES, Hilcorp was the largest methane emitter in the country in 2019. That year the San Juan Basin made up 65 percent of Hilcorp’s total methane emissions. Free from scrutiny by shareholders and the public, Hilcorp quietly absorbed Conoco’s dirty problems from the past. And the emissions are all still there, hanging above the San Juan in a persistent cloud that satellites spot from space.

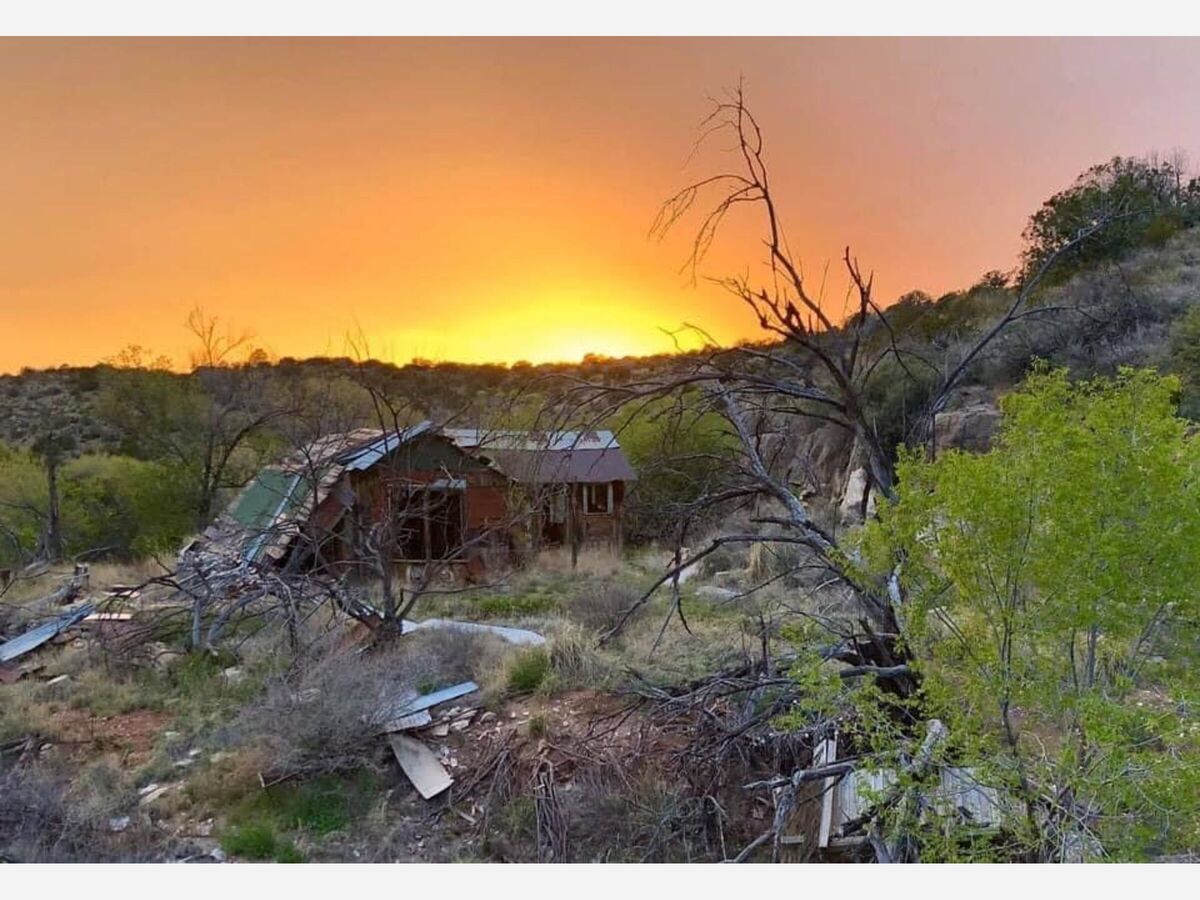

A Hilcorp natural gas operation sits in the middle of a canyon in the San Juan Basin.

A Hilcorp natural gas operation sits in the middle of a canyon in the San Juan Basin. Few in the San Juan Basin are as preoccupied with the continued environmental impacts from oil and gas as Don Schrieber. A Farmington native, 72-year-old Schreiber has watched various companies come and go from the region, from the 1950s when El Paso Gas owned most of the town, to the days of Burlington Resources, Conoco and now Hilcorp.

Now retired to a ranch in northwest Rio Arriba County, Schreiber has a front-row view of 122 Hilcorp wells scattered around the nearly 6,000 acres of dry rangeland that includes his land, grazing permit land and adjacent public land.

When Schreiber and his wife, Jane, first bought the ranch, there were 86 wells in the area owned by Burlington Resources and then ConocoPhillips. Back then, the couple was trying to establish a holistic ranching model. They spent most of their days on horseback, rotating their cattle to allow the native grasses to recover and regrow on the landscape. But as the wells started to multiply, so did the impact on the delicate grassland they were trying to restore.

“We were so focused on moving these grass plants closer together and then they just come in with a bulldozer and go over all of it,” Schreiber said.

The Schreibers worked with both Burlington and Conoco on a few methods to reduce the wells’ surface impact. They devised plans to reduce the overall land footprint of the gas operations by allowing beneficial vegetation to regrow along the edges of well sites and combining multiple wells on a single pad rather than across multiple areas.

When Hilcorp came, those collaborations stopped, Schreiber said. The company wouldn’t heed his concerns and only called to inform him of a new well or to deny his requests. Seeing that working with Hilcorp wouldn’t be an option, the Schreibers sold their cattle. Though they still lease their land and do some sustainable ranching work, they’ve focused much of their efforts on fighting oil and gas.

“We gave up our dream of creating a sustainable ranching model because we thought if you want to make an environmental impact, stopping a well is really what’s important,” he said.

Don Schrieber points out a natural gas well meter from 1953 — one of the oldest in the area of his ranch in the San Juan Basin. Schrieber, a rancher turned activist, has pushed energy companies to reduce their impact on the land.

Don Schrieber points out a natural gas well meter from 1953 — one of the oldest in the area of his ranch in the San Juan Basin. Schrieber, a rancher turned activist, has pushed energy companies to reduce their impact on the land. It’s difficult to determine the exact environmental repercussions that the oil majors’ exit had in the San Juan. Emissions data from both the EPA and New Mexico’s Oil Conservation Division are self-reported by industry and usually based on estimates rather than actual measurements. (The state also recently overhauled its emissions rules for the oil and gas industry, which, if successful, will greatly reduce the amount of methane and other harmful gasses that producers release into the atmosphere.)

In the absence of hard data, what is clear is that Hilcorp and the spate of other private gas companies that now dominate the San Juan have inherited a basin full of leaky, declining well infrastructure. And for the most part, the company seems to be keeping it that way. The overriding business model in the basin has shifted from companies looking to boost growth to those seeking to profit from lingering decline.

While the major companies used to plug wells as they became unproductive — sealing them and then reclaiming the land — the practice began to wane in the San Juan basin in 2014 and, even more, in 2017, when low-cost operators like Hilcorp began buying up wells.

Rather than retiring low-producing wells, companies like Hilcorp usually spruce up the old wells to increase their output or let them sit, without any interventions, trickling out small amounts of gas for a low profit. About half of Hilcorp’s wells are considered “stripper wells,” meaning they produce fewer than 15 barrels of oil or 90,000 cubic feet of gas per day, a fraction of what high-producing wells yield. Though stripper wells produce only a small percentage of the oil and gas sold on the market, recent studies show that they make up a disproportionate amount of the industry’s methane emissions.

Other types of clean-up operations have also stalled or been forgotten. New Mexico’s Oil Conservation Division, the agency responsible for regulating oil and gas activities, fined Hilcorp nearly $1 million last fall after finding that a pump system meant to remove toxins from the land at one of the company’s well sites was simply not functioning. The pump had just been switched off and left off.

“Their management is remote, so I’m not even really sure they know what they have on the ground,” said Mike Eisenfeld of the San Juan Citizens Alliance, a local environmental group.

Residents say they’ve been left with a sense of abandonment, but typically decline to speak on the record, citing a fear of reprisal from an industry where most of them draw their salaries.

Major oil and gas companies are known for throwing their money around in their operations, in politics and in their communities.

According to Handler, big oil companies are usually conscious of their public reputation, spurring them to spend big on safety and redundancies.

“They would gold-plate things, spend a lot of extra money just to get a little bit of an extra redundancy,” he said.

For much of the history of the San Juan Basin, this lavishness was the status quo. Oil and gas companies not only poured money into their operations, but also gave some back to the community. Schreiber remembers the 1950s when El Paso Natural Gas built everything in town from the roads to the houses. In more recent decades, companies like BP and Conoco shelled out for new buildings at the local college and sponsored nonprofit campaigns.

“ConocoPhillips wasn’t always the best environmental steward,“ Schreiber said, reminiscing. “But at least they were involved in the community.”

Even today, Farmington’s working-class feel is often interrupted by vestiges of oil major extravagance that pop up in odd places around town.

San Juan College’s school of energy has top-of-the-line labs and a robust fossil and geology museum.

The town’s baseball field, Ricketts Park, was built to a standard that matches most minor league stadiums.

The old Conoco building is one of the nicest in town, made of glass and metal and encompassing more than 114,000 square feet of office space.

But the school district has lately taken over Conoco’s building after it sat mostly vacant for years. Donations to the United Way dropped by more than 30 percent between 2016 and 2019. While the organization still gets a few thousand dollars every year through Hilcorp’s employee giving program, the institutional donations it once got from Hilcorp’s predecessors have completely halted.

In recent years, local governments hit by declining tax revenues have had little choice but to put their efforts into boosting other economic sectors.

“After a decade of downturn, we realized that something had to change,” said Nate Duckett, the mayor of Farmington. “We had to find some other economy that didn’t rely on the boom and bust cycle.”

Since taking office in 2018, Duckett has concentrated many of his efforts on developing the economies for outdoor recreation and retirement communities and on making Farmington more appealing to remote workers. Though he and other community leaders are still hopeful that oil and gas could spring back, increases in prices and drilling activity haven’t delivered the same benefits as they once did.

Rig counts are indeed up in the San Juan Basin today. But even as oil and gas prices spike, the modest uptick in activity is a far cry from the mega-booms of the past. The industry is changing, businesses are automating a lot of processes, which means they hire fewer employees.

Ricketts Park in Farmington.

Ricketts Park in Farmington. Ken Hare, a real estate developer and former member of the Bloomfield city Council, said that even as he welcomes another boom, he worries that slight pick-ups in the industry might quash what local will there is to change the economy.

“Bloomfield is the picture of what happens when you put all your eggs in one basket,” Hare said. “But it’s a tough mindset to change.”

And no matter what benefits might occur from an oil and gas boom, the environmental and social impacts still remain.

In November, Schreiber took a drive just up the hill from his ranch to the Hilcorp well that the Oil Conservation Division had fined just under $1 million several months earlier. According to the OCD, the problem at the well has since been fixed, but on this day the pump was silent and appeared to be abandoned.

For Schreiber, these oversights and the persistent neglect have convinced him that this final stage of oil and gas development in the region is far worse than whatever came before. He and others are fighting for reforms. But he’s not sure anyone is really listening.

“It’s a very lonely and powerless feeling, fighting this fight,” he said.

Lindsay Fendt got her start covering the environment as a reporter for The Tico Times in San José, Costa Rica. She covered human rights, immigration and the environment throughout Latin America before moving to Colorado in 2017 for the Scripps Fellowship in Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado. Before joining Searchlight Lindsay worked as a freelancer and is finishing a book about the global rise of murders of environmentalists.

https://checkout.fundjournalism.org/memberform?org_id=searchlightnm&cam…